The Sunday News

Richard Runyararo Mahomva

Dear Reader

Last week, I promised that we will be back on our critical engagement with literature. My apologies for not living up to my promise.

One ardent follower of the column gave feedback to that proposition — indicating that there was need to return the sanity of this page to its academic rooting away from the grime of the political.

However, circumstances have compelled me to indulge on the subject of filth (politics).

Surely, it’s a dirty game, but it’s an unavoidable definition of being. In its grubbiness it’s still a science. Its dirtiness makes it an interesting discipline.

In fact it’s a decorated science — political science. Its students are observers, they evaluate the consequences of the contestations it renders to its players.

So the dirt of this science must be critically examined and objectivity remains the centre apparatus of interacting with the inputs and outputs of this discipline.

As a budding disciple of political science, this period has taught me that credence is not won by assuming the propensity of the popular.

Some veterans of the discipline were up in arms and gun-blazing promising their audiences that Zanu-PF was going to be defeated.

Let alone, it’s now clear that some trusted mouth-pieces of political analysis have deflated from objectivity.

The burden that comes with being perceived as vanguards has landed our grand analysts of yesterday and masters of the discipline to sub-alternity. This is because it sounds fashionable to address elite audiences and think that they represent the popular will.

This election was eye-opening, it taught me that an individual’s wishes do not translate to the ultimate outcome of political processes. I have learnt that one can hate a political party, but an individual’s abhor of an institution does not undermine the credibility to a multitude.

Likewise, I have learnt with much awe that views of a selected geographic divide do not universally shape the thinking of a nation and a people. What have our politicians learnt? What have the supporters of the politicians learnt?

There are two pertinent lessons I got from this experience, in fact, the election refreshed my memory to the basics that politics must be accepted as “what is” and not “what should be”. Understanding this shapes objectivity, it even serves one the burden of depression. After all, politics is about ideas in competition.

Let this be a lesson to the young and old, particularly those credited as political scientists — to whom this piece is addressed.

Dear Scholar . . .

As the battle to catalyse sober African intellectualism continues on this weekly leaf; there is a need for unrelenting rethinking of thinking. In fact, it is the rudimentary essence of liberated intellectualism to unremittingly strive to deconstruct anti-narratives.

At the same time making sense of those ideas sadistically categorised as irrationally pro-establishment. This is because Zimbabwe’s political space has proved to be resistant political truisms peddled as facts.

In other words, there is a need to disentangle the given demonisation and ostracised imagination of the nationalist side of the overall African story whose thematic cosmology is undermined by Western intellectual bigotry through the mediums of sponsored reason (Ranger 2004; 2005).

That is the same African reason conveniently used whenever the Europeans want to appropriate our great minds in a bid to “internationally radicalise them”, the same way they have done with many of our great minds.

Indeed, Africa has been stripped of African reason(ing) — with her knowledge(s) categorically undermined as “indigenous” with limited if not any value outside the post-colonial “zone of non-being”. This is the reason why Africans are in an endless search of identities buried in the past.

This is why for some reason we have found ourselves pretentiously running away from Western knowledge traps in the interest to be decolonial. In so doing, the process collapses upon arrival at the immediate side of the seemingly redemptive leftist (Marxism) galaxy.

However, this does not invalidate the overall significance of the left epistemic paradigm of liberation as Africa’s thought-centre of re-ordering the order of an ugly past (Fanon 1960).

On the left side, Marxism is embraced as a haven from the Western bruises of dehumanisation supremacy fragmentation of Africa by a deliberate mechanism of stagnating the continent’s growth potential (Rodney 1973).

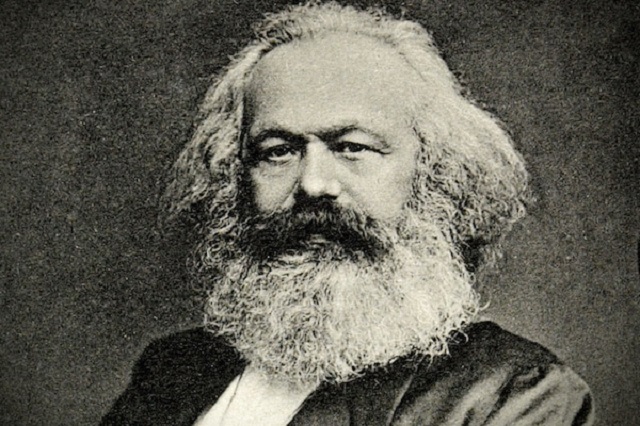

On the left side, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels are unchallenged makers of this liberating pedagogy. This explains why early post-colonial Africa was largely Marxist; even prior, the search for liberation across the continent was respectively solicited through Marxist tutoring of the masses.

Of note, the sublime pan-Africanist cleavage of the struggle to be free remained with its demarcations clearly drawn out.

However, some giant sectors of the African thought mischievously attempted to alter the density of pan-Africanism/ nationalism to what they called “African-socialism” — or “scientific-socialism” as espoused by Nkrumah. Clad in his rebellious Eurocentric pedagogy Nkrumah writes:

The term “socialism” has become a necessity in the platform diction and political writings of African leaders. It is a term which unites us in the recognition that the restoration of Africa’s humanist and egalitarian principles of society calls for socialism.

All of us, therefore, even though pursuing widely contrasting policies in the task of reconstructing our various nation-states, still use “socialism” to describe our respective efforts.

The question must therefore be faced: What real meaning does the term retain in the context of contemporary African politics? I warned about this in my book Consciencism.

Eastern-factor in the genealogy of Zimbabwean intellectualism

In pursuit of the African Living Law —through the Second-Chimurenga (Mahoso 2017), the ruling Zanu-PF was supported by China.

On the other hand, the Soviet Union had a similar bilateral contact with PF-Zapu. This gravitated the historical bedrock of ideological bias towards socialism for both anti-Rhodesian nationalist movements of this country.

However, pan-Africanism was the key source of influence to our fight for freedom in this country (Mahomva 2014). To date, pan-Africanism continues to be one logical tool for nation-building in Zimbabwe (Mahomva & Moyo 2015; Mahomva & Tshabangu 2016).

The post-independence euphoria was characterised by enormous homage pronouncements to socialism. As a result, public goods’ equity and distribution processes were modelled in the interest of maintaining an ideological rapport with socialist values in translating in Zimbabwe’s erstwhile public policy. This was believed to be the era political-economy par-excellency in some quarters, while other scholars maintained a discordant view (Mandaza 1986).

In 1991, Dr Ibbo Mandaza and Prof Lloyd Sachikonye produced an antithesis angle of the much political embraced exposition of the time.

Their book, The One Party State and Democracy: The Zimbabwe Debate, characterised the then Zimbabwean political-culture as ambiguously entrapped in the search for ideological belonging in the middle of the capitalist and socialist crossroads. The Zimbabwean Government of 1980 had to consolidate the gains of its socialist political-economy code. On the other hand, land hunger remained a crucial political question whose answer resided in the radical revisitation of the Chimurenga values.

This eventually resulted in the land reform and it’s unique contribution in the creation of a radical anti-establishment discourses. Now the debate was no longer about socialism. Coming to the fore, was the human rights and democracy debate.

In one old article, published in this paper I described the human rights and democracy discourse as an expression of borrowed mindsets: The challenge of borrowed mindsets is a threat to social-science indigenous knowledge generation.

It is a cancer to the memory of our present to the next generation justified to view us as defunct heirs of the liberation struggle.

This calls for urgent intensification of indigenous knowledge vacuum filling in the midst of the misnamed globalisation centred academic projections of post-coloniality especially in the case of Zimbabwe (Mahomva 2016).

Also at the centre of this democracy and human-rights debate is the theme of our failed nationalism if not fragments of our nationhood than its unitary components: It is sad that identity as a social construction now builds our negative perceptions for one another. As such a good initiative can be dismissed because it was facilitated by X and not Y.

This is the reason why Africa is at war with herself because her children consider themselves as emblems of contradictions shaped by politics, religion and ethnicity.

Before people consider themselves as Africans they are defined by their affiliation to these contradictions namely politics, religion and ethnicity.

There are a lot of points of reference that can be used to explain this problem confronting Africa which has led to so much wars and division of the continent’s people.

We may not realise that Zimbabwe just like other African countries is at war with herself and the reason is politics, religion and ethnicity (Mahomva 2016).

Today our war in Zimbabwe is a war of polarised ideas. The merchants of this crisis are the enlightened. Coming from beneath right up to the dawn of a promised dispensation we need to think anew and hold to account those who lead us.