The Sunday News

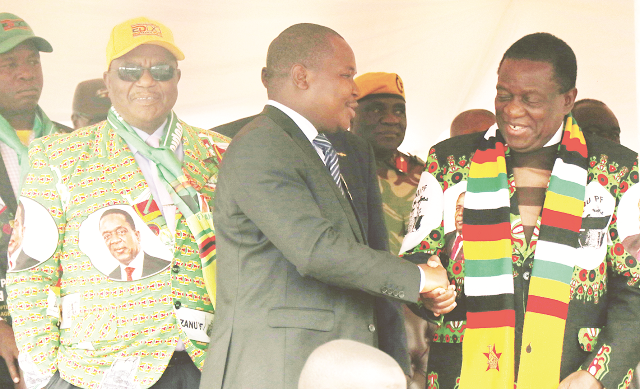

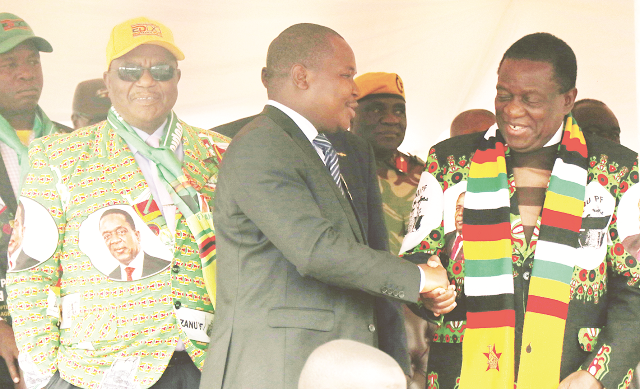

President Mnangagwa congratulates Chief Mabhikwa after he received heifers at the launch of the Matabeleland North Province Command Livestock and Fisheries Programme at Arda Jotsholo in Lupane on Friday. Looking on is Vice-President Chiwenga (left)

President Mnangagwa congratulates Chief Mabhikwa after he received heifers at the launch of the Matabeleland North Province Command Livestock and Fisheries Programme at Arda Jotsholo in Lupane on Friday. Looking on is Vice-President Chiwenga (left)AFTER Operation Restore Legacy which paved way for the new political dispensation in the country, there is perhaps no better way to make sure that the process reaches its ultimate goal than choosing the path of servant leadership as the guiding principle among the political elite.

As Popo Maja (2017) would put it “the theory of vulgar individualism and fetish corruption has (had) triumphed over the political firmness and sharpness of the leadership . . .” Maja could have been talking about events elsewhere, yet Operation Restore Legacy was also primed at addressing such ills, among others. And President Mnangagwa then came in and championed the adoption of servant leadership in both party (Zanu-PF) and Government. Servant leadership is an age-old concept, a term loosely used to suggest that a leader’s primary role is to serve others.

It was first mooted by an ancient Chinese philosopher and writer. He is the reputed author of the Tao Te Ching, the founder of philosophical Taoism, and a deity in religious Taoism and traditional Chinese religions. Lao-Tzu wrote about servant leadership in the fifth-century BC. “The highest type of ruler is one of whose existence the people are barely aware . . . The Sage is self-effacing and scanty of words. When his task is accomplished and things have been completed, all the people say, ‘We ourselves have achieved it!’” Of servant leadership, Lao Tzu says:

“Do not look only at yourself, and you will see much.

Do not justify yourself, and you will be distinguished.

Do not brag, and you will have merit.

Do not be prideful, and your work will endure.”

And in another text of his colossal works, Lao Tzu educates us thus:

“The wicked leader is he who the people despise.

The good leader is he who the people revere.

The great leader is he who the people say, “We did it ourselves”.

Soon Teo adds that Lao Tzu illustrates the power of servant leadership by using the analogy of streams and seas. By staying low — like a sea — the leader is able to receive and amalgamate, just like the seas do to the water from the countless streams.

The leader can stay low with the power of humanity, which is demonstrated by the deep respect for others. The soft power is a lot more effective than the wielding of authority of a leadership position. Leaders are to serve, not to dictate. Leaders are to empower, not proving himself to be better than his people.

According to M J Manala (2014), servant leardership focuses on serving “the other”, which resonates of an African leadership experience in which leaders “personify the order of the world and the harmony that enables its life to continue for the benefit of humanity” (Smith 2004:23).

Smith et al (2004:80), citing Laub, say: “Servant leadership is an understanding and practice of leadership that places the good of those led over the self-interest of the leader.” Servant leadership values and develops people, builds community, promotes the practice of authenticity, providing leadership for the good of followers and the sharing of power and status for the common good of each individual, the total organisation and those served by the organisation. The serving, caring, sharing and developing conduct of the leader are central in the servant leadership model, says Manala.

A servant leader has to display special skills like listening receptively, persuading and articulating and communicating ideas effectively (Smith et al 2004:82). They are selfless and want to give of themselves. They are actually slaves of the common good. Mofokeng (1983:VII), citing Fanon, says: “We are nothing on earth if we are not in the first place slaves to a cause, the cause of the peoples, the cause of justice and liberty.”

From the very moment he was thrust into the highest office in the land, President Mnangagwa pledged servant leadership saying he was ready to work with progressive Zimbabweans to rebuild the country. The duty to transform the economy, he said, is a collective effort that requires the involvement of all Zimbabweans.

He pledged to reach out to the international community to canvass their support in rebuilding the economy.

“I pledge myself to be your servant . . . I appeal to all genuine, patriotic Zimbabweans to come together, we work together. No one is more important than the other. We are all Zimbabweans. We want to grow our country. We want peace in our country.

We want jobs, jobs, jobs! We need also the co-operation of our neighbours in Sadc, the co-operation of the continent of Africa, we need the co-operation of our friends outside the continent. That we shall achieve. I am already receiving messages of co-operation and support for us to grow our economy.”

And six months down the line, he has achieved a lot with investors arriving in the country on a daily basis and the international community warming up to the country’s engagement and re-engagement efforts. A lot more is happening on the ground, with people in the countryside witnessing a shift for the better through Government programmes like Command Agriculture and Command Livestock.

There is no doubt that President Mnangagwa has struck the right chord with the masses. He has been waving his magic hand, reviving industries in towns and cities, where employment has been created. And last Friday, he took it a step further, handing over 1 444 cattle to villagers in Matabeleland North, after handing over 1 666 cattle in Matabeleland South in recent weeks through the Command Livestock programme.

And while in Lupane, he became part of the locals by speaking with them and not to them. He underlined that by using the local language, IsiNdebele, much to the amusement of thousands at the rally. This writer was among the bumper crowd at Somhlolo Stadium in Lupane. “Ah uyakhuluma (he can speak in Ndebele), uyamuzwa? (do you hear him?), kuyezwakala akukhulumayo (he speaks a lot of sense), ngu-President sibili (he is a real President)” These were some of the responses from the crowd as he gave his speech, punctuated by English, Ndebele and Shona.

Of course, he had in previous rallies in Gwanda and Bulawayo threw in some IsiNdebele words here and there, but he chose Matabeleland North to go full throttle, just to emphasise key points, something that went further than driving the message home but also showing that he is a people’s person and relates to everyone in every corner of the country.

In doing so, President Mnangagwa demonstrated that he was ideal for servant leadership and puts himself at the same level with the masses, and also celebrated our diverse cultures as a people, yet underlining that we belong together, and in unity and togetherness, the future is bright.

He urged Zimbabweans to shun corruption and underlined some of his key points in IsiNdebele. “Amasela asiwafuni” (we don’t want thieves). He urged people to shun violence and hate speech “inhlamba asizifuni”. He implored people to work hard, saying devolution would benefit each and every province: “Sifuna ukuthi inotho iye ebantwini”.

Peter Ives (2004), writing about the power of language and describing Antonio’s Gramsci’s use of language says; “His use of language as a metaphor enables him to develop the rich concept of hegemony that addresses the crucial and complex tension to paraphrase Marx, between, our being constrained by our historical conditions, and yet being human agents capable of mobilising and organising to change our world. Expressing this tension in the terms of contemporary social theory, Gramsci’s focus on language helps address how our subjectivity is constituted by forces external to us, and yet, at the same time, we as subjects make choices that collectively determine our lives.”