The Sunday News

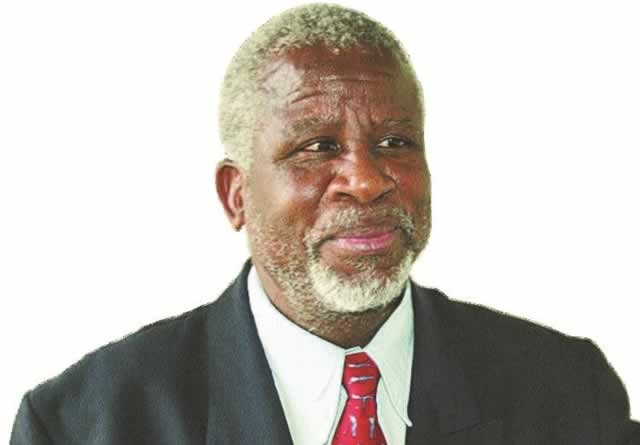

Pursuant to last week’s submission, this article is a continuation of the first half of Pathisa Nyathi’s paper presented at the 2015 Reading Pan-Africa Symposium.

Stage 2 Chasing After Shadows: Intensive Documentation of Cultural Practices and History

As pointed out above I already had written a piece or essay relating to African spirituality, actually a rejection of African spirituality in favour of the Christian religion. Notably, there was no documentation in Stage 1. Now I was a teacher endowed with a fair grounding in the natural sciences to explore the world from a dual perspective. Initially spending a lot of time imbibing in the Queen’s tears, I soon found myself plunging more and more into matters of African spirituality which opened new vistas and inquiry into African perspectives. This was some initial grounding and introduction to the African world, with its own science, art and craft.

In this period I got introduced to the works of Professor John Mbiti and his ideas on African spirituality, fertility and continuity. I also did Science of Religion and Anthropology, both of which fired my interest in African cultural practices and the underlying philosophy and what later I would prefer to call cosmological or philosophical underpinnings. I was becoming more and more patriotic and Afrocentric in approach and orientation. A sense of pride in being African was cultivated in me.

That was the time of serious documentation, of reading and writing. As far back as 1981 I had already contributed a poem, Till Silence Be Broken to a poetry anthology edited by Musaemura Zimunya and Xavier Kadhani titled And Now the Poets Speak.

It was a time when we held high hopes for our political independence. It was a time for celebration and jubilation. Towards the end of the 80s I got involved with the Zimbabwe International Book Fair (ZIBF). I sat on its board on account of my being Zimbabwe Writers Union (ZIWU) Secretary General. ZIBF then was Africa’s premier book fair. Issues relating to writing, publishing, protection of intellectual property, book promotion and development were dealt with. I got exposure to the entire book industry: writing, editing, book design, book marketing, book selling, the publishing industry and the enabling environment for the book chain and its downstream industry. Workshops for writers brought together eminent writers from all over the world. I rubbed shoulders with the likes of Wole Soyinka, Chinua Achebe, Ngugi wa Thiongo, Ama Atta Aidoo in addition to our own local writers such as Shimmer Chinodya, Charles Mungoshi, Barbara Nkala and later Yvonne Vera, among several others.

This was the time of explosion in my documentation of both history and culture. I felt some inner urge to write. At one time I tried to emulate Ngugi and wrote Ndebele history in the SiNdebele language. Vice-President Joshua Nkomo launched my first serious book Igugu LikaMthwakazi-Imbali YamaNdebele: 1820-1893. Mambo Press was my publisher. More books in the series came: Uchuku Olungelandiswe and Madoda Lolani Incukuthu. Longman published more of my books including school texts. Soon I found myself publishing with Reach Out Publishers, an offshoot of Shutter and Shooter in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa.

At this stage I was concentrating on churning out books that documented cultural practices. I would not define that period as documentation of indigenous African knowledge as I now hold a view that cultural practices devoid of their cosmological underpinnings are short on qualifying as IKs. This period was useful in generating a body of knowledge that I would later analyse and interpret till I got to a stage when I realised there was something more fundamental beyond the cultural practices. To understand the African and appreciate why he does what he does the way he does including his ceremonies and his rituals it is imperative to dig into the cosmological underpinnings of his actions.

At the political level this was the stage when I did several biographies. Longman commissioned me and others to write short biographies on the national heroes. I did a biography of Masotsha Ndlovu. Then I worked on George Silundika, Edward Ndlovu and Nikita Mangena though Longman had chickened out. I was now neck deep into the liberation heritage. I should say at the time I was confining myself to a narrower view which did not see a fuller or broader perspective which took into account the machinations of competing world powers. However, I was beginning to question approaches such as those of Professor Masipula Sithole who saw our struggle as struggles within the struggle. With a limited vision I was beginning to see some hidden hand. I was refocusing on the intended role of détente and the interests that US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger had been pursuing. I sought a better understanding of the causes of the 1963 split within the nationalist movement and compared that with the formation of the MDC in 1999. However, I still needed more literature and access to intelligence to take a more definitive position in navigating and seeking to understand the motives behind political action at both national and international levelsThat would come in Stage 3 when I would then see through the thin veneer of international political intrigue and how at national level some people dance to the whims and interests of powers that pursue thinly disguised neocolonialism.

Stage 3: Individuals Perish, Humanity is forever: A Period of Re-awakening

This was a period of disillusionment, one of re-wakening resulting from access to a large body of literature, both my own (built during Stage 2) and others as I continued to read other people’s works. I bought a lot of books, especially after being exposed to people like Professor Terence Ranger who had a colossal collection at his Oxford home. I have always believed that metal is sharpened by metal. In similar vein, a mind is sharpened by another mind. We cannot sharpen mind on rock — it will simply perish! Discussions, in particular with the Reverend Paul Bayethe Damasane and students from the USA that I used to lecture, sharpened my wits, and improved my intellectual agility and dexterity. When a mind has other minds bouncing off it, it is not exactly the same after that. Where questions are asked, he who tries to provide answers emerges the greatest beneciary during the process of inquiry. Over the years I have had several students who were doing undergraduate studies, masters degrees, doctoral degrees come to interview me. Out of the process I have emerged intellectually empowered. Their minds have been bounced off mine which emerged greatly enriched all the time.

At this juncture I sought to understand the motives behind behavior; the meaning inherent in behaviour and the worldview that lay behind, drove and informed cultural behaviour. I was seeking the cosmological underpinnings. While the Reverend Damasane lectured at Lupane State University (LSU) he challenged me to come and present a talk on symbolism to his students. That turned out to be my launch into the 3rd stage. The numerous cultural practices that I had documented were subjected to a new mental inquiry — one that sought meaning behind the cultural practices. I was deliberately Afrocentric in approach. For me it was no longer a question of getting into the shoes of the African. After all, he had no shoes for one to get into. It was imperative to get into his mind and fathom how that master of our bodies operates as it directs and influences our cultural behaviour and ritual and ceremonial actions.

The Reverend Damasane and I took it upon ourselves when we drove either to Harare or back to Bulawayo to discuss the worldview of the African as expressed in his cultural practices: ideas about the moon phases and how these impact on cultural practices, the symbolism and related symbolic manipulation as happens when rain is being prayed for. Symbolic manipulation is as real as manipulating the material world. In simple terms, the non-material accesses and manipulates the material. This expresses the important idea of unity within nature as encapsulated in the circular design. We scrutinised the African concept of time and arrived at the expression “iphambili leNdebele lisemuva.’

In the same period I was appointed to the National Commission for the Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH). ICH itself deals with the intangibles inherent in objects, for example their design, and ritual actions. This was a move, a migration from the material plane to a spiritual realm which facilitated the explanation and interpretation of the African cosmology that lies behind the cultural practices and actions. One year I undertook a trip to Nairobi to observe the ICH Inter-Governmental Committee (IGC) in action. That was yet another opportunity to appreciate the spiritual or intangible realm.

I was lucky to be nominated to be part of the Zimbabwean delegation going to Algiers where there was a cultural expo. All African countries, save for Morocco, were represented. At that time I was already interested in the chevron design. I moved from one country pavilion to the next. In all of them the chevron design was represented in one form or another. That I saw as a Pan-African phenomenon being exhibited in particular, in the visual arts world. Later still, I attended a cultural meeting in Addis Ababa where I was exposed to the breathtaking design of the AU headquarters. On some walls there were motifs that were characteristically African. I was eager to know the meaning for these. We visited the shops that sold artefacts. Once again the decorative motifs were there begging for interpretation. Once back home, I with Kudzai Chikomo penned a book that commemorated the golden jubilee of the AU, formerly the OAU. I remember well that it was during the flight to Addis Ababa that it suddenly dawned on me that what I had hitherto called a chevron was in actual fact a circle. I then made a bold declaration that the circle was nature’s organizing design.

Soon I sought meaning behind the circle. I came to the conclusion it represented unity, dynamism, movement, rhythm, fertility, continuity and eternity, the concepts introduced to me by Professor John Mbiti. I was now firmly within the world of Welsh Asante’s seven aesthetic senses in African art and the astronomy of the Dogon of Mali and the theories of Credo Mutwa of South Africa. I tried without success to see some fundamental differences between philosophy, science and spirituality. I looked at the trees, the human anatomy, and the heavenly or cosmic bodies. In all these I found the universal design to be the circle. That idea was enshrined in the AU commemorative book. It dawned on me that to document African cultural practices was like chasing shifting shadows. It was more important to identify and pin down the cosmological underpinnings. I saw clearly how understanding an idea takes a cyclical form. Each time an idea is revisited there is a better understanding of it. It was here that I witnessed the transformation from preoccupation with cultural practices to obsession with the philosophical underpinnings.

While the documentation of indigenous knowledge continued unabated, its form changed. I was looking at the same issues that I looked at in Stage 2 but differently from both the native commissioners’ and early missionaries’ perspectives. I was no longer content with a mere mechanical description but sought the more fundamental and underlying cosmological considerations. I looked at San rock art in a different light.

The art can only make sense and meaning if interpreted from a San-centric point of view. The mind of the San, being first and foremost that of an African, must be understood. How is it be possible to appreciate the product of a mind that we do not understand?

Fortunately, when I reached this level of understanding I had become a publisher. I could publish books that some publishers would have hesitated to publish. A series on Zimbabwe’s Traditional Dances was started in conjunction with the Jikinya Traditional Dance Festival organized by the National Arts Council of Zimbabwe (NACZ). When I had to design the logo for Amagugu International Heritage Centre (AIHC) the state of my mind was captured. Both the circular design (the earthen pot) and the chevrons (stylised) were captured. I am on the verge of writing about the meanings behind the decorative motifs on painted walls in the Matobo District. The “My Beautiful Home — Comba Indlu Ngobuciko” has provided me with the opportunity to look closely at the motifs that the rural women have executed on their hut walls. What is being communicated by the women, I want to know? Through the project I should be able to document the indigenous knowledge inherent in decorative motifs and go deeper to bring out the meanings behind the motifs, in other words, the worldview that is being expressed.

What politics can we espouse that is different and a stranger to our worldview? How can we negotiate this position given the shenanigans and intrigues of world powers that seek to derive maximum benefit, both political and economic, from our countries?

Just how independent are we to navigate our worldviews and cosmologies that seem to run in the face of western traditions on scholarship and academy? just how?