The Sunday News

Richard Runyararo Mahomva

FOR the past few weeks, I have been discussing the consequential impact of Zimbabwe’s political outlook and how it has shaped evolution of knowledge production.

Much of the matters I discussed explicitly indicated the extent to which Zimbabwe is gradually ascending the far-stretched heights of decolonial thinking.

I drew my examples from the country’s current political discourse; paying particular attention to how regime-change ideas have no place in Zimbabwe’s market of ideas. However, for a change, I thought that it will be interesting to take a different dimension this week and engage Pathisa Nyathi’s views and experience on indigenous knowledge. The following is the first half of Pathisa Nyathi’s paper’s paper which was specifically prepared for the 2015 Reading Pan-Africa Symposium convened by Leaders for Africa Network (LAN).

Pan-African thought: Inspiration behind the generation of indigenous knowledge

We search for knowledge for a purpose. Further, we search for a particular knowledge that is presented in a particular fashion, orientation and ideological position and grounding. How we search, couch and present that knowledge sometimes takes an ideological position. It is true that I have, over a number of decades, generated a lot of material relating to indigenous knowledge, more specifically perhaps African indigenous knowledge. This has taken the form of history, culture, biographical and liberation heritage books, newspaper articles in the Sunday News, Umthunywa and other newspapers and occasional academic papers presented at workshops and symposia both locally and abroad.

The question that we ask is why does an individual commit himself or herself to a relentless search and documentation of indigenous knowledge? I have therefore seized the opportunity to introspect and place my own life and work under the microscope with a view to understand better what knowledge I have been documenting, the transformations that have taken place as I searched for that knowledge and the emerging ideological, philosophical and cosmological underpinnings that have followed my search for indigenous knowledge.

May I seek your indulgence distinguished participants in taking you down memory lane to pick on landmarks and thrusts in my life of documentation to highlight the motivations that have been behind the work and the commitment. I have for that purpose, created three categories, call them developmental stages through which my search for knowledge has gone. Stage 1 starts with early life following birth in 1951 in rural Matabeleland, at Sankonjana in the Matobo District up to my completion of training as a Science teacher at the Gweru Teachers’ College at the end of 1973. This early life and its wider political, spiritual, religious impacts had a strong influence on my perspectives regarding what indigenous knowledge I was going to seek and document.

The second stage spans my teaching career and working life in general from 1974 to about year 2008. This was the period of intense generation of indigenous knowledge when I penned several books, did several biographies, wrote history books in SiNdebele and plays for school production. The period is characterised by the acquisition of knowledge that was no different from that presented by the early missionaries and native commissioners in colonial Southern Rhodesia. I undertook intensive interviewing of several elderly custodians and doyens of our culture: Gogo Matshazi, Hudson Halimana Ndlovu, Gideon Joyi Khumalo, Msongelwayizizwe Khumalo, Mbangwa Mdamba Khumalo, Wilson Lethizulu Fuyana, and Benson Mpungazathi Fuyana, inter alia. Save for one, the rest have since been promoted to glory.

For the liberation heritage I also carried out several interviews and sampled numerous sources of relevant literature.

However, it was interviews with individuals who participated in the liberation struggle. The interviews gave me a great sense of satisfaction leading to the unravelling of certain important political lessons in particular getting to appreciate the impact of the hot cold war on local and regional African politics from before the formation of the Organisation for African Unity (OAU) to the present. Among the interviewees on this front were the following: Ernest Dube, Jack Amos Ngwenya, Clark Mpofu, Misheck Velaphi Ncube, Abraham Nkiwane, Livingstone Mashengele, Dumiso Dabengwa, John Maluzo Ndlovu, Jane Ngwenya, Abel T Siwela, Welshman Hadane Mabhena, Luke Mhlanga, Moffat Hadebe, Saul Gwakuba Ndlovu, Mike Masotsha Hove, Sikhwili Moyo, Andrew Nkulumo Mafu, Tapson Nkomani Sibanda (Gordon Munyanyi), Eddie Sigoge, Elijah P Nyathi, Isidore Ernest Dube, Stephen Jeqe Nkomo, among several others.

During this stage some considerable mass of information and knowledge had been gathered whose analysis and interpretation led to a new stage where there was more emphasis on the cosmological and philosophical underpinnings behind the knowledge that I had hitherto documented. The world’s political contestations were seen against the background of competing world interests and not necessarily our national interests.

The 3rd stage starts about 2009/10 when at both cultural and political levels there is some reawakening and interrogation of some issues resulting in the emergence of new perspectives and interpretations . At the cultural level there is marked migration from documentation of cultural practices to engagement with the worldview and cosmology of the African within which Pan-Africanism is couched and understood.

At the political level there is some alertness and attentiveness to world economic interests at play to shape our own politics. It is the sort of politics that explains the gulf between the Cassablanca and Monravia groups during the build up to the formation of the OAU in Addis Ababa in May 1963. World economic interests play out at the local national political front.

In all these experiences I realised the cyclical nature of development, be it in the acquisition of knowledge or higher levels of understanding the same issues. I came to realise that linear progression and expression of development is both unnatural and unrealistic. With this general introduction, I am now in a position to provide more flesh to each stage.

Stage 1: A Time of Gathering: Coming Under Influences From a Varied Environment

Before going to a western oriented primary school belonging to the Salvation Army, I came face to face with African spirituality. Just outside our home rain making ceremonies were conducted. My father was an accomplished herbal practitioner.

The Kalanga humba spiritual phenomenon was practiced with my paternal grandmother as a medium who I was sent to summon for the rituals at our home village. When we went to school we were introduced to Christianity which demonised African spirituality. Western ideas and concepts were filtering through and at times were at odds with African ideals, values and principles.

My father, who was a story teller, introduced me to both the material and spiritual worlds of the African. At one time he had been to the Njelele Shrine to consult the Fertility Deity on issues of fecundity. The fireside stories painted an African world which was glorified and believed in. After primary school I then went to Mazowe Secondary School, a Salvation Army institution just north of Salisbury, now Harare. The emphasis here was to consolidate the Christian teaching introduced at the primary school. I was away from home for extended periods, thus I was cut off from the African experiences that had been introduced at a tender age. After all, that was the missionaries’ idea of ensuring that the gullible Christian converts did not turn into sliders. The songs implored us to do away with our ancestral spirits,

Lahl’ idlozi lahl’ inyoka;

Lahla amanyala wonke;

Woza kuMsindisi manje . . .

The brass band was impressive and all this succeeded in erasing some African impressions made earlier on.

It came as no wonder therefore that my first writing, which won second prize at an essay competition organized for schools in Mashonaland was titled “No God in the Cave.” This was an obvious rebuttal of what my father had told me. Our English Language teacher one Major Margaret Moore from the USA was an excellent teacher and tried to remodel our lips so that we could acquire an American accent.

This is the teacher who developed in us an interest in politics. She was our librarian who provided us with political books:

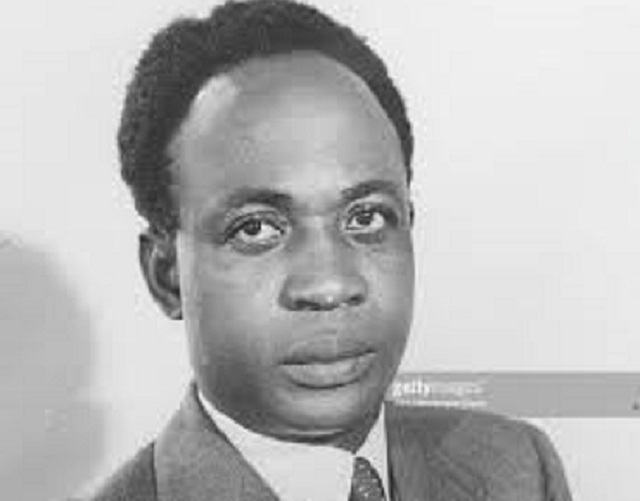

Patrick Keatley’s Politics of Partnership, Ndabaningi Sithole’s African Nationalism, Kenneth Kaunda’s Zambia Shall Be Free and Solomon Mutsvairo’s Feso. There were newspaper clips posted on the school’s notice board about Zapu and its leaders, about Zanu and its leaders, the death of Samuel Tichafa Parirenyatwa, the OAU and some of its leaders such as Emperor Haile Selassie, Kwame Nkrumah, Jomo Kenyatta, Hastings Kamuzu Banda and Julius Nyerere, inter alia.

We were presented with facts without analysis and interpretation. The broader political picture was not presented to us. Our Pan-Africanism was no more than the political unity of Africa and enumeration of its political leaders. No cementing ideas, ideals, principles and ideological orientations, let alone the political and economic interests of competing world powers, were given to us. The war of liberation that was raging on was perceived as a national issue seemingly without the world’s politics playing out at the local level. I remember in December 1974 dreaming about Nkomo and Sithole leaders of Zapu and Zanu respectively, being released from detention. Indeed, they were released the same month. It was such spiritual revelations, characteristic of African spirituality that would intensify in the 3rd stage when my very close friends and I referred to them as “radar.”

This was a period of participating in African cultural experiences, a period of a foretaste of what I would, in the second stage, be documenting after some research in order to come up with a fuller rendition of the fading cultural practices.

What is important though is that a basic foundation for critical influences in later life had been laid: political interest and liberation heritage, cultural practices and experiences, interest in books and literature (reading and writing), interest in the performing arts, African spirituality, Christian religion, and western education with a bias towards the natural sciences plus an inquisitive and inquiring mind.