The Sunday News

Phathisa Nyathi

TODAY we turn to the arts of the Venda. This we do as we observe striking similarities between what their arts express and what we have been saying is expressed by the arts at Great Zimbabwe.

It is our view that interpretation of Venda arts by Anitra Nettleton (1984; Dewey 1997) is more Afro-centric and more in agreement with our thrust. Sexuality is given emphasis. Symbolism, aphorisms, imagery and metaphors are given due prominence in line with African expressions.

Nettleton notes that the Singo King’s praises refer to “ngwena madzivha,” crocodile of the pools. Sometimes we fail to appreciate the connection between the ‘‘pool’’ and the crocodile and thus miss out on the fundamental and underlying messages being expressed.

Let us start with the symbolic pool being referred to here. “For the Venda, as for the Shona, pools are associated with the origin of the world, in which the original man emerges from a pool of water, and the animals are vomited from the stomach of a python (Frobenius 1973; Nettleton 1984). In an earlier article we made reference to the Dziva/ Siziba people and indicated that at the centre of the “pool” is not the literal physical pool but rather a metaphorical pool which is a euphemism for the female genital.

Among the Sotho, their origin myth points to a place known as Ntswanatsatsi, thought to be in the Orange Free State in South Africa, a pool or marsh fringed by reeds.

The image being painted here is pretty clear, as a way of negotiating a treacherous terrain characterised by vulgarity and obscenity. Ethical and moral considerations demand that appropriate language, imagery, aphorisms and metaphors be used in order to remain within the boundaries of morality, decency and probity.

Hopefully, this is becoming clear as what is referred to would normally remain under the tongue. The reeds fringing the perennial pool are a reference to pubic hair. To arrive in this world we emerge from the very perennial pool that is fringed with reeds. A biological statement is being made.

When Ndebele children asked their mothers where they got new babies from, invariably the answer always was from a pool of water, abantwana bathathwa esizibeni. Origins from a pool of water are not unique to the Venda.

As pointed out above, the Ndebele too used the same imagery to explain origins of humanity. For the purposes of our Journey to Great Zimbabwe, the relevance lies in sexual expressions as hinged on the idea of continuity, endlessness, eternity, perpetuity and immortality. It is only through sexual reproduction that humanity attains the all-important idea of continuity. Out of the figurative pool, we emerge in a process that ensures succession and replacement of the dead.

Among the Nguni people lineages are referred to as inhlanga (singular, uhlanga). Which is your reed, literally? Once again, we are back to expressions of sexuality for reeds are an integral part of the female element. Among the Venda, the imagery attains greater clarity and association. “In aphorisms used in the domba (female initiation) there are references to the khoro, the main public court, or more specifically, as Lake Fundudzi with the king/ crocodile at its head or centre with the python around its periphery; this lake imagery pervades many of the objects used in the courts of the kings (Nettleton 1984). Once again, the pool or lake image is this time more specific and linked with initiation of girls who have reached puberty, a stage that preceded biological processes that guarantee continuity of the human species.

Linking the King and the community itself is significant. The king epitomises the community and when that community subsists his royal rule lives through the community.

The girls being initiated will produce progeny, an expression of continuity fulfilled and the royal line rules over the extending and expanding community. A community needs a leader or ruler while the King on the other hand needs a community. It is a fish and water relationship.

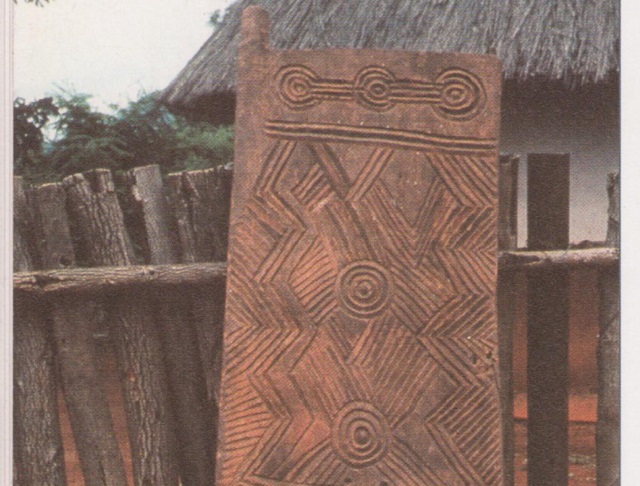

We now turn to the objects of the Venda and see what is expressed by the motifs that are executed through carved relief. The objects that are resplendent with decorative motifs include the king’s door (vhoti), drums (dzingoma), xylophones (mbila) and divining tools, inter alia. “The objects share a repertoire of abstract decoration and a common iconography based on the symbolism of the lake, a central icon within Venda cosmology (Dewey 1997).” Let us, at structural level, observe some commonality between the stone walls at Great Zimbabwe which are also found in the land of the Venda.

Thulamela is one such similar cultural stone edifice. Rather, our interest lies in the motifs, their underlying messages and how these compare with what exists at Great Zimbabwe.

We turn to the king’s door, vhoti. The King’s hut, pfamo, has an elaborately decorated door referred to as ngwena, the crocodile.

The carvings are said to be a symbolic marker of burial and succession rites of Singo kings. On the door are chevrons and concentric circles which are taken to be the eyes of the crocodile, ‘‘mato a ngwena’’. We have, in earlier articles, rendered expressions behind the chevron motif and patterns. We are in essence back to expressions of sexuality within which is embedded the concept of continuity or fertility.

What is striking even more is the identical arrangement of two chevron lines or linear patterns. Pointed ends point in opposite directions and, in the process, create a visual rendition of a crocodile, albeit without a head and tail. A stone wall of the Great Enclosure and the king’s door are, in that regard, identical both in terms of arrangement and the underlying meaning. This ties up with other motifs in terms of commonality of expressions.

The idea of continuity is encapsulated in wooden doors, circles, the pool and the crocodile itself. Another motif on the wooden door is what is being perceived as diamonds. This is a good example of how we tend to look through cultural lenses. What is here being seen as diamonds are, in Africa, two chevron motifs arranged back to back. No diamonds about it.

Equally, the circles bear the same meaning as given in earlier articles. A circle has no beginning and no end. It is an expression of continuity and fertility or sustainability of a human community. Having more than one circle is a result of repetition and enhances aesthetics as posited in African Aesthetics. We shall, in the next article, try to link the chevron pattern and the crocodile and argue that the two share a common expression and hence both Venda arts and arts at Great Zimbabwe express the same underlying messages.

For now, let us deal with the python imagery. We see it, the python, surrounding the pool and domba initiates take a chain formation that resembles a python.

We are, once again, back to the situation where male and female elements co-exist. The python has dual expressions. When a new home was established, a python skin was dragged on the ground to mark the boundary of the new home. A python symbolises strength, protection and defence. On the other hand, the same python symbolises a phallic reptile, on account of its cylindrical shape.

While the pool or lake is clearly a female element, fertility requires that there be two opposite but complementary elements. The pool image of the Venda, that pervasive icon, tallies with what is found at Great Zimbabwe. Need we refer to the snake and woman in the Bible? The Biblical world was an African world with its metaphors, aphorisms, symbolism and images. Perhaps you will now begin to see the story in a new light.

Finally, there is a belief, at least among the Ndebele, that a new python emerges from the backbone of a dead python. In fact, people who consume medicine with python parts face problems when they get very old. They simply will not die easily until some ritual is arranged to effect their death. The python therefore symbolises eternity, much as the pool, chevron, circle and the crocodile do.