The Sunday News

Pathisa Nyathi

SOMETIMES we take art for granted and, in the process, completely fail to appreciate its role within society or community. We have been told art is expressive culture.

It has the capacity to fathom the unfathomable while also accessing the inaccessible.

Art is sometimes driven by the creative instinct in human beings, a trait that humans possess in varying quanta.

What we experience we sometimes wish to expose and share.

What we experience through the eyes of our creative minds, we seek to bring to the fore, to hold and to share, and to celebrate through artistic expression and representation. Art expresses art. Art celebrates art.

This is by way of introducing and extending thoughts and ideas regarding Mukomberanwa’s stone sculpture which we are using to introduce ways through which Africans have celebrated that which belongs in the private domain.

Among ideas to be celebrated is attainment of continuity, eternity and endlessness. There are traditional dances which celebrate fertility, such as the Jerusarema Mbende.

Other dances are prayerful and beseeching, used during prayers for rain. Both Woso (Amabhiza) and Wosana (Njelele Dance) belong to this category.

Just how do we begin to celebrate fertility of humans in the absence of fertility of the land? Humans, indeed other life forms too, thrive through ingestion of the progeny of Mother Earth.

When the agricultural season has yielded plenty of food, celebrations ensue. A good example is the Mbakumba traditional dance of the Karanga people which primary schools will be performing in 2019 and 2020 as part of Jikinya.

The holding of the dance follows the conclusion of harvest. Art comes as a performance which is accompanied by feasting and drinking.

Only when Mother Earth is fertile, can we hope to attain our own fertility. Continuity, eternity and endlessness are driven and powered by the presence of rain which lies behind fertility of the land.

Apparently, there is perceived equivalence between rain and semen. The phenomenon of rainmaking relies on symbolic manipulation of sexuality where some imaginary man is up there in the sky and relates to Mother Earth in some remote-controlled erotic encounter where rain is synonymous with his semen following ejaculation enticed and induced by dancing women.

The Mayile Dance of the BaKalanga displays this symbolic manipulation which lies at the heart of ensuring Mother Earth is fertilised.

The celebration of continuity is celebration of sexuality. Here lies the irony and contradiction which is navigated through recourse to art.

Sexuality is attended by ethical, moral and honourable social dictates. Not so long ago we hosted teachers from Ihlathi High School in Bulawayo.

One cultural aspect we found ourselves having to grapple with was expressions of sexuality as these abound in the Ndebele language that they teach.

Emphasis was given to how Africans cope with matters sexual and yet remain within the domain of morality and sanity.

The one aspect which fitted in well with Mukomberanwa’s stone sculpture was recognition that Africans do swear in anatomical terms.

There was agreement that women’s genitals are never mentioned even as one swears. If done, it could spark some altercation.

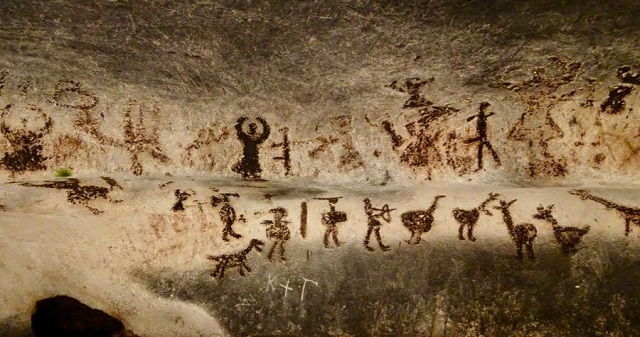

The same is not true with regard to male sex organs. A quick look at the art traditions of the San reveals the same. The San drew males whose sex organs are not covered; if anything, their male organs are erect.

You however, never as a general rule, come across female sex organs. This is taboo in the African ethical field.

One teacher asked why iron smelting was carried out in concealed places.

Her observation was correct but the teacher was at a loss as to why the numerous iron smelting sites within the Matobo Cultural Landscape are generally found in inaccessible places.

All that it took was to bring to the teachers’ attention that iron smelting symbolises the sexual act in humans. Humans never engage in sex in public like donkeys.

Similarly, iron smelting, bequeathed with symbolic male and female elements engaged in sexual intimacy, has to be carried out in hidden sites which correspond to closed doors of bedrooms.

Moving forward with the idea of sexuality, it was noted that one avoids vulgarity and obscenity by referring to the male organ as a neck, intamo.

One swearing would, accordingly say, “Ntamo kayihlo!” In the African ethical context this is understood to refer to the male genital.

Similarly, with regard to women, swearing would go like this, “Mlomo kanyoko!” This amounts to total congruence with Mukomberanwa’s stone sculpture.

What we see is a symbolic ‘‘mouth’’ through which the inaccessible is accessed and applied to obviate and bypass obscenity.

Imagine the revulsion and outcry that would have broken out if the sculptor had crafted a true image of a female sex organ.

The lesson we draw here is how Africans from different cultural backgrounds make use of the same artistic tools and designs to traverse the treacherous terrain of vulgarity.

In language symbolism is applied. In sculpture Mukomberanwa has been creative and innovative.

The mouth has taken the position of a ‘‘mouth’’. The mouth is acceptable and not associated with the profane and can be exposed to the public which is not the case with the “mouth.”

The ‘‘mouth’’ denotes sexuality and must belong in the private domain, concealed and covered as it constitutes nudity which is anathema.

Continuity is underpinned by the coming together of male and female elements in some erotic encounter.

It is observed that even where the elements occur separately there’s need to resort to artistic manipulation such as mimicking, alteration and relocation.

If this is so, it goes without saying that the higher level where the complementary elements are depicted in sexual encounter there is even higher demand for artistes to call upon the best of their creative armour and come out unscathed.

At the level of Architecture, such as at Great Zimbabwe, we have male and female elements occurring separately.

This is not accurate and realistic enough as continuity, endlessness and eternity are concretised when the two elements relate to each in a particular way; sexual intimacy.

It is a way that is crafted to meet the dictates of sanctity, morality and must be one that circumvents vulgarity and obscenity.

Art, be it poetry, or prose; sculpture, painting, engraving, drawing or architecture, has the capacity to deal with the profane and sacrilegious and, in the process remain pious.

We believe we have laid sufficient foundation to a point where we are ready to grapple with our national emblem — the Zimbabwe Bird.

We are alert to the fact that if we just plunged into the contentious field of manipulated symbolic sexuality, many, especially those not au fait with African Art and African Cosmology, would be quick to dismiss our ideas as a lot of humbug and sexual perversity of African natives, if for once, they avoid seeing nigger jumbo mambo. We push on despite, for our target audience lies in the future.