The Sunday News

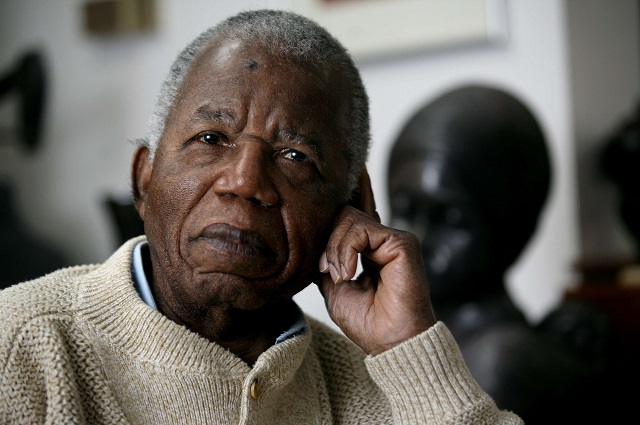

Cetshwayo Mabhena

Struggles for liberation in the world cannot be sufficiently studied or discussed without reference to a powerful black thinker, Frantz Fanon. Frantz Fanon was born in the Caribbean island of Martinique on 20 July, 1925 and he died on 6 December 1961. After a good 55 years after Fanon’s death, psychiatrists, philosophers and revolutionaries still rely on Frantz Fanon’s concepts and nuances.

Critical theorists, post-colonial theorists, humanist Marxists and decolonial thinkers are still beholden to the mental furniture of Frantz Fanon.

The global academy is peopled by a multiplicity of gurus in Fanonian studies, among them biographers of Frantz Fanon and interpreters of the wealth of his philosophy. One reason for the growing interest in Frantz Fanon as a liberation thinker is the planetary nature of his thought that was shaped by a short but thorough life of learning, armed struggle, medical practice and philosophical writing. Planetary thinkers are those thinkers of the world who have been on many sides of the geographic and ideological divides of the world to an extent that they are able to philosophise on planetary issues.

At 19, as a French citizen by colonisation, Frantz Fanon fought in the French struggle against the Nazis. Injured in battle, Frantz Fanon was given a prestigious award for extra-ordinary bravery. After the war he studied medicine in Frantz and there in France Fanon realised that he was not really a Frenchman but a usable and dispensable Negro.

In disgust, he left France for Algeria. When the Algerians erected a fierce uprising against French colonialism in 1954, Frantz Fanon went back to the trenches, this time against France for the African people of Algeria. In one black body, Frantz Fanon combined a medical doctor, psychiatrist, soldier and philosopher, and this rich complication and sophistication reflects itself in his philosophical thought.

In Fanon is a soldier who got injured in war and also caused injuries, but also spent a number of his days healing those that had been physically injured and mentally traumatised by war. Fanon is the philosopher of liberation who celebrated as much as he condemned violence, leaving Fanonian philosophers and students lost as to where exactly he stood on violence.

Clever philosophers have decided to deal, rather, with types of violence or violences in the thought of Frantz Fanon, not just violence. As I write, something importantly disturbing and disturbingly important has happened. Some industrious French librarians and archivists have unearthed a body of unpublished essays by Frantz Fanon that are presently being published and translated to other languages including English.

Once again the world of ideas and knowledge will breathe some fresh Fanonian air. Fanonists, among them the prophets, philosophers and professors who have turned Fanon studies into a religion and an industry are warned that some of their deeply held conclusions might be up for dismissal. The Fanon that has long been lost to us has been found and is about to be disseminated.

The Place of Translation in liberation

A large part of the projects of slavery and colonialism was the systematic “murder” of the languages and histories of the enslaved and the colonised, what Ngugi wa Thiongo has called “epistemicides” that accompanied the genocides of conquest.

The archives and cultures of the enslaved and the colonised peoples of the Global South were erased, silenced and distorted in calculated epistemicides that are sadly, still going on today. The wisdom and philosophies of the enslaved and colonised peoples that has found itself in English, French and other languages of Empire is mainly that which was screened and vetted by missionaries and later day editors and publishers as permissible. A huge archive of the stories, histories, myths, legends and philosophies of the people of the Global South is still imprisoned in oral traditions and the few books that are rendered in indigenous languages.

The preservation and promotion of indigenous languages and knowledge systems is a liberation project on its own that African governments and policy makers have to take seriously. Further to preserving and promoting indigenous languages and Indigenous Knowledge Systems, epistemic liberation requires that the philosophies and histories of the former slaves and former colonised peoples be rendered in world languages so that they participate in the global dialogue and conversation about life and liberation. Chinua Achebe described this global conversation as the troubled “dialogue between the North and the South” that must surmount a multiplicity of colonial impediments.

It was to be Chinua Achebe again, the liberation philosopher, who famously noted that it is creative and revolutionary to empty the English language of its imperial sensibility, its Eurocentric content, and load it up with African sense and sensibility, and use it to rebuke imperialism and curse imperialists.

This habit of adopting tools of imperialism, adapting them and using them for the project of liberation has been described by liberation and decolonial thinkers as “border thinking” and “epistemic disobedience,” which are the arts of purposefully breaking the cultural rules of Empire in order to project the views and experiences of its victims.

Translating the Zimbabwean Archive

On creativity and culture, Zimbabwe boasts a bounty of wealth of literature that is rendered in English. I wonder if faculties of humanities and department of languages in Zimbabwean universities and colleges have considered a project in translated literature that is in indigenous languages into English. This possible project will not only extend the Zimbabwean publishing and cultural industry, but the world will be richer with more Zimbabwean thought, creativity and philosophy that remains provincialised in our mother tongues and is screaming to be globalised.

If a novel like N.S. Sigogo’s Umhlaba Umangele, was to be rendered in English, even the British would read in English how villagers in Zimbabwe suffered and resisted the theft of their fertile ancestral lands by settlers. And not only for its political message, the novel is also an exhilarating classic of sheer narrative pleasure and pulsating poetry. Mayford Sibanda in Umbiko KaMadlenya, an epic novel, explores one of the world’s intriguing political succession stories. The ideological, political and military battle for the succession of King Mzilikazi; as rendered by Mayford Sibanda is the true stuff of movies.

Besides the narrative strength and aesthetic beauty of the novel, the political philosophy that is found in the conversations of the historical characters that Sibanda fictionalises and brings to life makes a joke of some of the best gems of western political theory and philosophy.

The entertainment value of P.N. Mkandla’s Abaseguswini leZomthalilo cannot be exaggerated. What has been ignored are the moral and ethical teachings of the stories that in a folkloric manner deploy animals as human characters.

Far better than the modern day cartoon strip and television cartoon scipts, the stories in that collection exude some of the richest wit and wisdom of African natives for the consumption of young minds.

Similar to Frantz Fanon’s greater liberatory philosophy that is being liberated from the French language and the libraries of publishers who were keeping or hiding the manuscripts, the philosophy and creativity of our elders that remains frozen in our mother tongues should be unleashed.

The world conversation on life, power and liberation, through translation, will be far much richer and powerful with the contribution of our stories and histories. Far too many Eurocentric fictions and myths have been circulated around as classic, while the real classics from the natives remain in orature and vernacular.

The translation of native classics into languages of Empire, far from being a loss, it becomes what French philosopher; Michel Foucault called an “insurrection of previously subjugated knoweldges” that vindicate the humanity and cause of the natives and the victims in the world.

Another gift to the world of knowing and knowledge that Foucault gave was his thesis of the “archeology of knowledge” which suggests the need to dig up hidden nuances and wisdoms in otherwise ignored cultures and traditions.

There is a scramble in the world for new sciences and arts, for novel theories and inventions. But, a slow look at our oral traditions and indigenous literatures reveals a lot to be rediscovered and unleashed.

Cetshwayo Zindabazezwe Mabhena is a Zimbabwean academic based in South Africa. [email protected]