The Sunday News

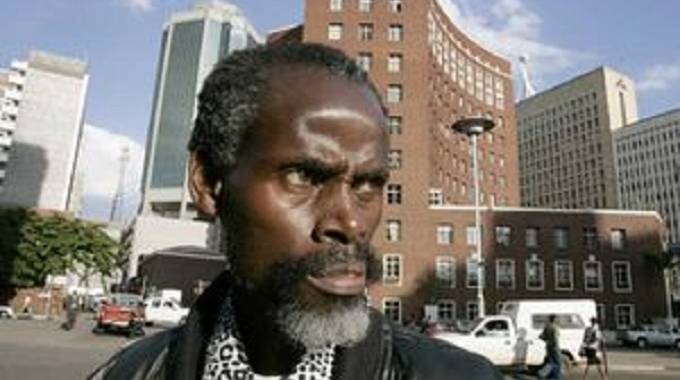

ON Monday 1 August the nation woke up to the news that arts doyen, Cont Mhlanga had passed away. As we remember the illustrious life of the renowned playwright and film maker, Sunday News reproduces an interview UKhulu had with Sunday Life Reporter, Bruce Ndlovu in March 2021, chronicling his life in the arts industry.

Bruce Ndlovu, Sunday News Reporter

FOR a man who has spent the best part of the last three decades in the spotlight, precious little is known of Continueloving Mhlanga’s personal life.

Sure, his professional life is familiar enough. As the founder of Amakhosi, he is the man who has almost single-handedly shaped Bulawayo’s arts and culture scene. He is the gift that has kept on giving, the gift that gave his nation Stitsha, that rare triumph of creative writing and production that was able to attain success both on stage and on the small screen.

He is the man that brought to the small screen Sinjalo, a comedy that dared to go where many others feared to tread, tackling thorny issues of tribe and bigotry and doing so while keeping a smile on viewers’ faces. He is the man that cast an eye into the future and came back with gold, dreaming up Amakorokoza, a production that predicted the rise of a class of men and women who would dig up the length and breadth of the country in search of its abundant mineral wealth. Despite all that, little is known about Mhlanga himself. This, he said, is deliberate.

“These are things that I don’t like talking about. I’m not the kind of person who likes his life splashed around in the papers. I want to be known for my work and nothing else. I’m an intensely private person and that’s why people don’t know much about my life.”

If Mhlanga has it his way, his life should be tracked from 1982, when Amakhosi was born in his backyard. This was when a supremely fit Mhlanga in his athletic prime, met a teenager by the name of Albert Mparura. This young lad asked to join the then karate doyen in his practice sessions and in doing so, laid the first seed for the birth of Amakhosi. Or the birth of Cont Mhlanga, given the fact that it is almost impossible to separate the two.

“The first generation of Amakhosi were young kids that were below the age of 17 years. Amakhosi was always an organisation for young people and that is the reason that we are still concentrating on people that are 19 years and younger. That generation of six young children started at the back of my yard. That generation of Amakhosi is the founding rock of the centre as we know it today.

“Actually, the karate club started by accident. A young kid called Albert Mparura from Nguboyenja used to see me practising around the neighbourhood. I was training in front of the yard and he would pass by our yard watching.

Then Albert asked to join me and I advised him to join a dojo and pay a subscription fee. He said he stayed with his grandmother and he could not afford to pay subscription fees. I told him to join me when I went out for our run in the early mornings and he did just that,” he said.

What was still unknown to Mparura was that he had got the ball rolling and that ball would roll on for the next four decades, and on its journey, it would mould the image of a city that would reinforce its reputation as the cultural capital of the country. During those first days in Mhlanga’s backyard, the arts were still far from the mind of the Kung-fu sensei and his six young protégés.

“His friends joined him and, in a week, we had six. In another week we had ten. Then I said let me work with the best and in a month, those six were always in the family yard. That is how it all started,” Mhlanga said.

Mhlanga credits his father, the city of Bulawayo itself and the politicians who ran the city’s affairs at the dawn of independence as his muse.

“There is no creative Cont Mhlanga minus three pillars he met in his early life. The creative Cont Mhlanga is a product of the City of Bulawayo. If there is no City of Bulawayo then there is no Cont Mhlanga. There is no Cont Mhlanga also without the influence of my father, who was a top brass politician. Thirdly on one hand I’m a direct product of the first generation of Zapu politicians that took over the running of the city from the white administration after independence. I’m a product of that triangle,” he said.

It was the work and influence of that triangle that led to Cont and his six protégés moving from his backyard to Mthwakazi Youth Centre.

“My father observed that these children were getting big in number so he said since they were now so numerous, we should take them to youth clubs in line with city council policy. That’s exactly what my father arranged with the then councillor of Makokoba, uBaba uBhule and the then Mayor of Bulawayo. There was a series of meetings at the time with politicians and that’s how the politics of Zapu came in. Eventually we were given the Mthwakazi Youth Centre and that’s where we started.

“That’s when the elders used Amakhosi to redefine community service and they were amazing in terms of the help that they gave us. We told them Mthwakazi Youth Centre was now too small for us and they reacted and found a place for us at Stanley Hall.

We got there not because we were clever or we worked miracles but because there was a lot of political play at city level and it was this political play that opened doors for us. Until now the city administration considered Amakhosi their project. Even to this day we are still riding on that. When we do something, we consult the city first,” he said.

As Dragons Karate Club resident at Mthwakazi and then later on at Stanley Hall, Cont and his students were obsessed with one thing and one thing only — making a Kung Fu movie inspired by the ones that they used to watch in community halls.

“We used to watch Kung Fu films, at what we called Dengo at Stanley Hall. City council halls were showing films and these were the in thing when we were growing up. There would be long queues to get into these community centres and that is when we thought that maybe the best way for us to raise money for our Karate Club would be to make a Kung Fu film. That was the major objective. Even today that is an objective because we have made everything except that Kung Fu film. The Kung Fu film that started everything,” he said.

Despite their desire and passion, the sensei and his Kung Fu loving ensemble faced one problem: they did not know how to write a story let alone one with complicated action sequences in it.

“The challenge that we faced was that we did not have a clue how to write a story or how to construct a story within a Kung Fu film. Then we were lucky in 1980 that the National Theatre Organisation, which was made up of mainly white members because black people were nowhere to be seen at that time, came to Stanley Square where we were practising and said they were there to conduct a workshop about acting. We didn’t even know what a workshop was.

I told everyone else to go home and I would go to the workshop. That’s when I discovered that this was what we wanted in our Kung Fu film — how to write stories,” he said.

From that accidental workshop attendance, Cont Mhlanga the playwright was born. After a brief flirtation with conventional drama however, it was not long before dreams of a Kung Fu came back flooding back into the young writer’s mind.

“Our first drama was Bantwana Bantwana and it did not have any Kung Fu in it. It was inspired by the workshop that I had attended. We hated making that drama because it involved a lot of talking. So, after we did it, we decided to do The Book of Lies which had a lot of action involved. We did not have money to do the Kung Fu films so we decided to do Kung Fu plays to raise money for the movie,” he said.

As time progressed, Mhlanga and his troops discovered quickly that karate plays were not bringing in enough money to make their dream of making a karate movie a reality. In fact, their flashy, action packed sequences on stage attracted a juvenile crowd that did not have much income to dispose of.

“Moving from karate drama was not only a conscious decision but a business one that we still use even today.

Remember our target was to make as much money to make a Kung Fu film. Our plays were not making money and we talked and decided that we should change to make more revenue. Tickets back then were divided between those that cost five cents for children and those that cost 10 cents for adults. We realised that we weren’t making a lot of money because the people that were buying our tickets were mostly children. We realised that adults did not like karate content. We researched around the city and we studied how adults entertain themselves on weekends,” he said.

A historian of note, Mhlanga has always been a meticulous researcher. It was those skills as a researcher that were to save the burgeoning club as they stared down the financial abyss.

“We then decided I would write the drama about a subject the Traditional Dancers Association liked and they would bring in the dance and choreograph. In the end I took Romeo and Juliet and adapted it into a play called Ngizozula Lawe. It was a play which infused a lot of music into it and we chose six of our best karate fighters at Amakhosi to mix with the dancers.

Kung Fu was mixed with traditional stick fighting. We practised at Saint Patrick’s and we unrolled the shows in community halls. The shows were now pegged at 30 cents and they were oversubscribed. We made a lot of money from them and that is when we moved from karate to the formal theatre that we are still doing today. It was purely out of business research. It resulted in our first tour,” he said.

Amakhosi was to rise to national prominence in the early 90s with the debut of Stitsha on national television, a production that announced to the country that Mhlanga and his merry band of talented youngsters had truly arrived.

By this time, they had not only travelled around the country but toured the globe itself, picking up invaluable experience that they brought to the small screen.

“While I was travelling abroad, touring with Stitsha, I was also engaging a lot with film schools, film productions and film studios and researching about what we needed to cross over from stage to screen. That’s how in the early 90s I negotiated with a Norwegian film company and I negotiated also with a funding company to get us started.

We also negotiated with the BCC to take over the running of Happy Valley Hotel in Nguboyenja which was near where I stayed. The hotel back then was defunct. It had everything that we needed to set up our first studio in Bulawayo.

“The studio was called Happy Valley Films. We brought in 38 young people who went full throttle into television production training. A proper full studio was set up for content production. That’s how we crossed over to the screen from the stage. It was all a co-ordinated process between us and the City of Bulawayo and it was during that process that we brought in ZBCtv.

We then took one of our plays Stitsha and redid it for TV. Working at Happy Valley planted the seed that we needed a cultural centre. That’s how the idea of Amakhosi as a cultural centre was born,” he said.

Mhlanga can safely lay claim to being one of the gurus of local theatre and television. Few artistes, dead or alive, can compete with his resume and in the city that shaped him, he is, at least in the world of the arts, treated like deity with barely a negative word said against him viewed as near blasphemy.

Despite this, as Amakhosi’s prominence has waned over the last few years, he feels like his contributions are belittled by know-it-all young creatives that believe they are better than the godfather himself.

“I always get amused when this new generation of creatives treat us as if we don’t know anything. The Google generation act as if we don’t know what we are doing. All this came about because we planned it. It was not by accident. Maybe they don’t find anything about us when they search online. But it is because we did it before Google,” he said.