The Sunday News

Bruce Ndlovu, Sunday Life Reporter

THE story of Cont Mhlanga’s early life at its essence, is really a tale about clothes.

When he was born on 16 March 1958, the man Zimbabwe would eventually come to know as Cont was only known as Mdladla Mhlanga.

Year later, in primary school, where he started to don khakis brought for him by his parents, he would go on to acquire the name of Cont. it was a name that stuck to him for the rest of his life.

“He was given names by two people. His uncle, Ndundamkhonto, who fought in the battles at Pupu gave him the name Mdladla because we are Swati and Mdladla was a Swati king before Tshaka’s time,” revealed his brother Styx Mhlanga, the late arts’ doyen’s brother.

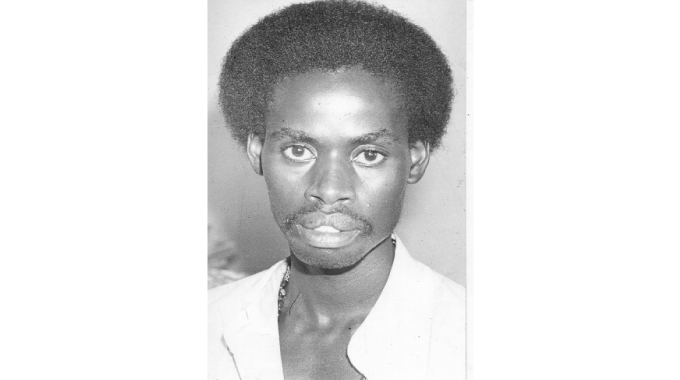

The late Cont Mhlanga

Mhlanga’s uncle might have drawn colonial blood on the banks of the Shangani but that uprising and others had been unsuccessful. So, when Cont went to school in his khakis in 1960s Rhodesia, the country was in the under the heavy boot of colonial rule, with the black majority losing not only its land but its culture too. The gains for the black majority were marginal and far and few in between. Cont was one of the few that gained something, albeit, it was only a new name.

“He started his education at Shabula Primary School but he didn’t finish his primary education there as he later went on to Fatima, a boarding school. That’s where he was baptised by the Catholics and given a new name because, they felt that Mdladla was an unchristian name. He was then christened Nicholas but in his class at school there was another Nicholas. The unfortunate thing was that both of them, like me, had tiny bodies so it was hard to tell them apart from one another. Both of them were also ‘characters’ so, in the end one was called Nicholas Littleberry and Mdladla was called Nicholas Cont,” Styx said.

The man who would go on to be the founder of one of the most remarkable and enduring arts institutions in post-independence Zimbabwe was horned and prepared for leadership at a very early age, due to the fact that he was the first-born child in the large Mhlanga family. Even in his humble, sometimes threadbare khakis, he was a boy that the rest of his family looked up to.

“When he was young, he was more matured than the other boys in the family. We come from a family with many boys and only four girls. Before the lord took some us, we had as many as 14 or 15 boys in the family. Mdladla was the first born in such a large family, he was the first born and that meant that the Mhlanga family, especially my father, my mother and my uncle, started gearing him for leadership at a very age. He was nurtured to lead the rest of us in the family,” Styx said.

A large majority of Zimbabweans were introduced to Mhlanga’s storytelling gifts when productions like Stitsha exploded from the stage on to the small screen in the early 90s. However, the by that time Mhlanga family had been in owe of his storytelling abilities for decades, to a point where his return from boarding school would be eagerly anticipated by his siblings. Sitting by the fireside in rural Lupane, he would electrify their evenings with tales of his adventures in boarding tales.

“He had a gift that he used throughout his life, which was storytelling. When he told you a story, whether he wrote it or by word of mouth, you would enjoy it. So, when schools closed, Mdladla would tell us a lot of stories. When schools were about to close, we would anticipate hearing his stories about boarding school. One of the tales he told us was about how, together with his friend, they had gone into the garden at Fatima and stole nartjies.

At mass the next day, a priest they called Mandevu came down the pulpit and headed straight to Mdladla and said in broken Ndebele, the lord does not like children that steal his nartjies. So Mdladla went for a long time without doing anything mischievous because he thought that the lord spoke to the priest directly,” said Styx.

Up to now, Mhlanga mainly wore khakis that that been brought for him by his parents. As left school and began his working life, bellbottoms and colourful shirts, the raging fashion back in the 1970s, now entered his wardrobe.

“When he left Fatima, because he had a small body, they wouldn’t allow him to be laborer. They asked him to wait for two years but the elders in the family were worried that he would become corrupted by the streets if he was idle for that long. They allowed him to work at Monarch where they used to make bags. He worked there until the mid-70s and at one time he was a hippie. He had an afro, would wear bell bottoms and leave his shirt half buttoned. He would play music by Jim Reeves and the likes of Jimmy Hendriks,” he said.

Hippies from that era were notoriously carefree and rebellious and Cont was not different. It was during this phase that stopped supporting Highlanders, a team that was dear to the hearts of members of the Mhlanga family.

“On the weekends, he would not miss a match at Barbourfields. However, even until his death he had a certain creative quality that always made him look for the next challenge, he left the team the whole family supported and went to Eagles. He was a rebel, so he rebelled against the family and went on to support another team but in the end, he came back to Bosso because Eagles was eventually relegated,” said Styx.

At independence, Mhlanga changed again. Out went the bellbottoms and rainbow shirts. Tracksuits and flat shoes were now in vogue, as Cont turned to the far east for inspiration, following the teachings of Buddhist Monks.

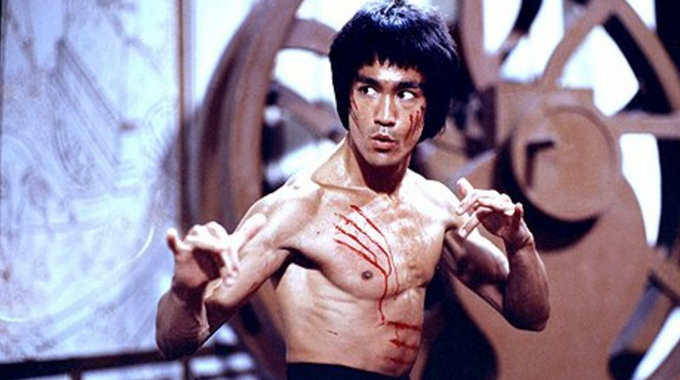

Bruce Lee

“He changed his life again near independence. At this time, he became spiritual and he was that way until his death. He started doing yoga, he would sit with his legs crossed and do meditation. Even the books he started reading were for monks. He only wore big tracksuits and flat shoes. He left football on weekends and he would go to McDonalds and Stanley square and watch movies featuring the likes of Bruce Lee. Because he had a gift for storytelling, when he got home, he would tell us about a film and it would seem as if we were also there. I would even retell stories about Enter the Dragon to others as if I had seen the movie myself,” said Styx.

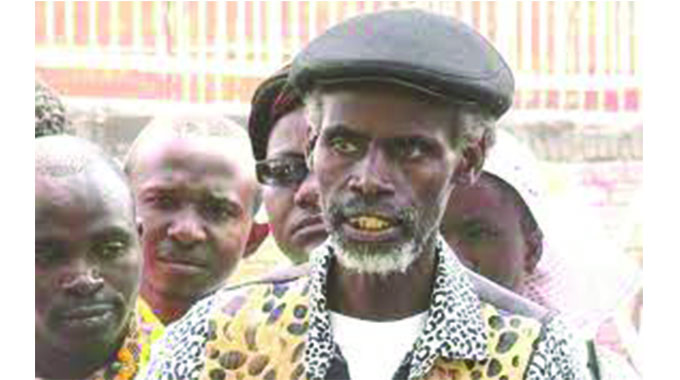

Soon, Mhlanga would meet theatre, a craft that would define most of his life. A waistcoat and a cap would from that point, became his signature look for almost four decades. It was a look that Zimbabweans got gradually became used to over the years. To many, it was as if Mhlanga had been born wearing a cap and a waistcoat.

“In the end, he accidentally discovered theatre. I can say theatre looked for him and he also looked for it, and they united. When he was into karate, his students called him teacher and I used to wonder what kind of teacher he was because he had never gone to a teacher’s college.

When he started in theatre, the whole town, and even in Harare, everyone started calling him malume. He had visions and dreams and the strength to convince other people to buy into that vision. When he came into theatre, at that time, he discovered a new way of dressing. Every outfit would have a waistcoat and a cap. That became his identity until he passed away.”