The Sunday News

Cetshwayo Zindabazezwe Mabhena

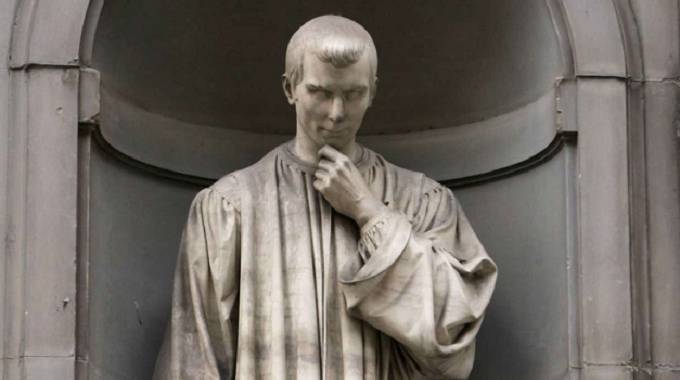

To refer to Niccolo Machiavelli as decolonial is to deliberately ask for trouble. It is to perform a kind of mischief that is likely to attract questions at best and condemnation at worst. Machiavelli’s reputation as a defender and celebrant of tyranny is stronger than a stigma and is almost as accepted as biblical truth. The Florentine philosopher, historian, playwright and diplomat has achieved a very bad name over the centuries. Tyrannical leaders have embraced him as their prophet, gangsters and Mafiosos have appropriated him as an inspiration, and democratic humanists have condemned him as a wrong model.

After his stint in jail for a felony 2pac, who had read Machiavelli behind bars, came out to call himself Makavelli. The enduring reference to Machiavelli as “Old Nik” is a moniker that establishes the thinker not as a disciple of the Devil but as Lucifer himself that stands for all the dark and bloody things under the sun.

I write the present short piece not as an apologia for Machiavellianism but an observation of how classical thinking has led to the misunderstanding and misinterpretation of great thinkers. Classics are those beautiful and great works of philosophy and art that stand the test of time and seem to get better and bigger as they get older. This piece is also a provisional response to a reader that contacted me to complain about my tendency to ‘mix things up’ and refer to Machiavellianism as a positive attribute when it is actually pure evil.

My observation and allegation is that Machiavellism is over and above everything decolonial in the sense in which Machiavelli actually opposed colonialism, imperialism and tyranny. I insist that, in the popular and regular sense, Machiavelli was not a Machiavellian.

Getting over the Crime of The Prince

The misunderstanding of Machiavelli and misinterpretation of Machiavellianism is rooted in his classic essay of 1513, The Prince. In that essay Machiavelli celebrates war and valorises political leaders that make promises and not keep them. He makes heroes out of princes and leaders that either caress or crash the people. A good leader is the one, Machiavelli suggests, who does not kill but also does not allow his enemies to live.

The Prince is considered the true manifesto of tyranny and despotism, and evil account, by its regular and random critics. A leader should know nothing more than he knows war and war should not be postponed but be carried out as regular duty. Moralists and other do gooders therefore clearly and rightly find Machiavelli undemocratic, ungodly and evil by all accounts. And that is where the problem starts but that is not where it ends. The problem is going on and it is the misreading, misunderstanding and misinterpretation of Machiavelli’s words. I am making a big allegation and challenging generations and canons of great thinkers on political philosophy and history.

Machiavelli did not mean everything that he stated in The Prince, and he says so. In a letter that he wrote to his friend Francesco Vettorri on 10 December 1513, from his exile, Machiavelli discloses that he has written a “thing.” He also states that there is the “thing” and the “thing itself.” Those of us that have read or played around with philosophy, especially Plato’s Seventh Letter will know that the thing is a shadow and the thing itself is the actual object.

We also need to know that before he became a philosopher Machiavelli was recognised as a satirist who wrote amongst other works the classical play The Mandrake, an exemplary work on irony, paradox and guile. In The Prince Machiavelli was satirizing and not affirming tyranny. The essay was written not as book to be published but a letter to an individual leader from whom Machiavelli needed a job. Lorezo de Medici was the Prince that had jailed and exiled Machiavelli after the Soderini dynasty was toppled in a coup in 1512.

When Piero Soderini fell the Medici family returned to Florence and took over power, punishing officials of the previous regime of which Machiavelli was a key member. Stubbornly, he still wanted the new regime to give him back his job, so he wrote an advisory letter that was supposed to be music to the ears of Lorenzo. Machiavelli actually says in the introduction to The Prince that his aim was to gain the favour of Lorenzo by saying what the new ruler would most love to hear. In that way The Prince was a deceptive, satirical and maybe Machiavellian job application that was written by a poor job hunting exile. The fellow had been reduced in political and economic status. He had taken to snaring birds to afford some meat for super. He says it himself that if there was anything the new rulers needed him for was his knowledge of history that he acquired through careful and strong reading. He was a technician of power that every regime that wants to survive would need.

The Prince is a classic of beauty and power that has for centuries been mistaken for a cold and dry philosophical treatise. On this, Isiah Berlin’s essay: The Question of Machiavelli (1971) and Antoni Gramsci’s treatise: The Modern Prince, vindicate my observation and allegation. Louis Althusser’s famous lecture of 1977: Machiavelli’s Solitude provides, perhaps, the most forceful argument in proof that Machiavelli is misunderstood and misinterpreted by those that read The Prince literally. The proverbial angels die in great heaven always when a satire is read and understood as a matter of fact script.

Against Classical Reason

Classics, in philosophy and in art are great and canonical works but they can be misleading. Those that have read Edward Said will agree that his book: Orientalism of 1978 is a classic but it is not his best work. Similarly, Things Fall Apart of 1958 is Chinua Achebe’s most famous and entertaining novel but it does not represent the depth and power of Achebe as an artist and a philosophical thinker. Closer to home, I am an African is Thabo Mbeki’s most beautiful speech but it is not the most powerful. Classics tend to be all poetry and little philosophy and political gravitas.

They tend to be beautiful but powerless in terms of their potential to change the world through message and meaning. Classical works almost always are beautiful and famous works that tend to conceal rather than reveal the actual thought of the writers and philosophers. The Prince is such a piece of work by Machiavelli that has concealed his other works like The Discourses and The Art of War where Machiavelli appears as a true and thorough going republican that was opposed to tyranny, violence and all forms of oppression. Classics are exactly true to their name, classy. They get classified above other works when they are not exactly the best. The Prince is a small part of Machiavelli’s work that has been mistaken for the whole. It is not even an organ but a cell mistaken for the body, I observe.

On the Persecution of Africa

One of the key messages of Machiavelli in The Art of War is that war is too important a subject to be left to the Generals and their soldiers, the people should be consulted and considered before arms of war are deployed. He says it that those political problems that can be solved by talk and negotiations should be solved that way otherwise war almost always leads to “the peril of the commanders” and misery for the populations. In the Life of Castruccio Castracani Machiavelli discourages war and pride in leaders, creating enemies and conquering all opponents leaves a leaders’s children exposed to enemies that want revenge when the leaders die or loses power. Conquest becomes a curse for the victorious leader’s children and descendants.

Winner take-all politics were despised by Machiavelli who preferred accommodation and compromise for lasting peace and prosperity. Flatterers and sycophants are profiled by Machiavelli as the greatest poison to power that should be avoided, and leaders should listen more to their critics than their praise-singers. My favourite essay by Machiavelli, the decolonial Machiavelli is: On the Persecution of Africa, where he condemns vandals from the West that were advancing imperialism, slavery and colonialism into Africa. Machiavelli opposed the abuse of power and use of impunity and cruelty. He had no respect for such princes as Lorenzo de Medic and would work with them only to dissolve their power from inside their regimes because above pride he loved Florence, the city state of his birth. There is truly no mixing things up in considering the decolonial Machiavelli, there is only straightening things up.

Cetshwayo Zindabazezwe Mabhena writes from Gezina, in Pretoria: [email protected]