The Sunday News

Cetshwayo Zindaba Mabhena

Ignorance is the foundation of all knowledge. There would be no need to seek knowledge if there was no ignorance. It is the power of ignorance and its many dangers that keep us knowing and that gives premium to knowledge.

And every knowledge, if it is knowledge, is a form of ignorance because it is knowledge against another or other knowledges that it ignores or dismisses.

To know is therefore, to ignore something that disputes or contradicts that which is known. It is for that reason that most really knowledgeable people begin to profess their knowledge by confessing the limits of what they know and their ignorance.

As a novice in the thankless academy I used to wonder why even the most famous professors of philosophy and history used to refer to themselves as students of philosophy and students of history.

It was not just good old village humility but deep intellectual fear that for the little that every expert knows there is a vast archive of what they don’t know and what lies ahead to be discovered and what will remain buried in the deep libraries of our collective ignorance.

The tired but very relevant cliché “God Knows” is not just an expression of confusion or that we have reached our wits end on a matter but a richly philosophical expression of the limits of what we know and the power of what we don’t know. What we don’t know we tend to lazily or fearfully surrender to God or other forms of metaphysical power and wisdom. That is why most of us like prophets and other diviners because they claim to know the unknown.

I make this brief reflection of the power and even beauty of ignorance in order to underline the gravity of knowledge and the importance of the freedom to know and the freedom to be known to know which has been denied blacks and other oppressed people of the planet. A big part of the enslavement, colonisation and oppression at large of black people relied on the myth that they are ignorant and therefore barbarians and natives that are not completely human. Ignorance is thus so feared. All knowledge making and production, epistemology itself as a province of philosophy is based on the fear more that the hatred of ignorance. Ignorance is imagined as a form of prison from which knowledge frees us. Such clichés as that the “truth shall set you free” cement the belief that ignorance and its cousin falsehood, falsehood is untruth and pseudo-knowledge, are a form of dungeon of darkness from which we urgently need to be freed.

The Freedom to be Free

Hannah Arendt is that clever Jewish and German woman that became the arch-philosopher of how humans can think through such dark times as the Holocaust. Thinking in Dark Times became one of her compelling essays after her 1951 classic, Origins of Totalitarianism. One of Arendt’s compelling arguments was that people that are prisoners of fear and are hostage to poverty are not free to be free.

Before a people can contemplate freedom and achieve liberation, she thought, they should be free from poverty and fear. Freedom from poverty and fear was therefore the ultimate freedom to be free. That creates an alarming possibility that people who practice politics and vote out of conditions of fear and poverty may not be true agents of democracy and liberation, something that must concern us in the Global South. That the electoral decisions of the poor and the fearful may not be legitimate and true decisions should scare fanatics of electoral democracy the world over.

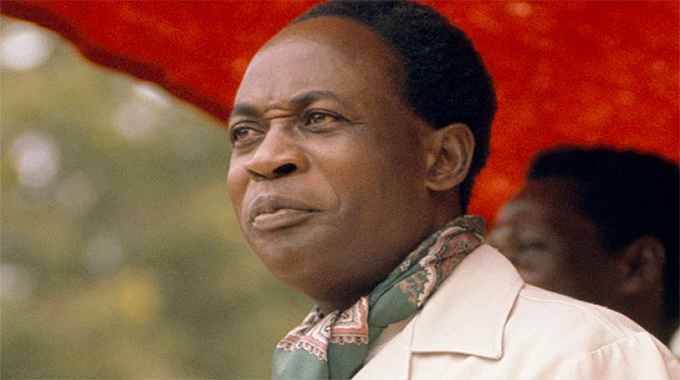

Thinking from inside the dark times of present Africa, Sabelo Ndlovu-Gatsheni, a decolonial philosopher, has added another angle to what the freedom to be free is. Gatsheni has thrown the cat among the pigeons, ukubeka induku ebandla, on that people may not be liberated without the achievement of epistemic freedom. Gatsheni does not only deepen Arendt but also complicates Kwame Nkrumah whose thesis was once that the political kingdom, political power, was the prerequisite for the achievement of liberation from colonialism and other forms of domination. The term epistemic freedom, once again, implies that the opposite is epistemic unfreedom, a kind of darkness and prison of sorts.

Epistemic Freedom

Gatsheni draws a bold line. If W.E. B. Dubois was right that the problem of the 20th Century was the problem of the colour line then that of the 21st Century is the problem of the epistemic line, he argues.

The problematic of epistemic unfreedom is the problem of our epoch in the observation of Gatsheni. In one stroke of argumentation Gatsheni collapses together Arendt, Nkrumah and Dubois. The epochal problem of racism, the colour line, that Dubois observed, that of poverty and fear that Arendt noted and the epical problem of political powerlessness that Nkrumah registered were all human prisons and darknesses that demand that we achieve first and foremost, epistemic freedom. Poverty, fear, racial domination as oppressions and parts of coloniality cannot be defeated with ignorance or epistemic unfreedom is the gist of Gatsheni’s provocative if stubborn argument. For us, otherwise to defeat coloniality we must first fundamentally know and understand first how the world works, and the nature of dominations and oppressions themselves.

Gatsheni opens our eyes in multiple and also very interesting ways. I, for instance, begins to connect the interest colonialists had in the ignorance of the colonised to the power of epistemic freedom. Colonisers feared the epistemic freedom of the colonised.

Colonisers did not only claim that the natives were ignorant but they also worked hard to cultivate the ignorance through colonial education systems and policies such as Bantu Education that South Africa is yet to recover from.

The ignorance or the mis-education of the colonised became the political capital of the colonisers. In his own pithy way, Steve Biko noted that “the greatest weapon in the hand of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed”. The oppressors of all shapes and sizes are interested in using epistemic unfreedom, ideologies, falsehoods, myths and propaganda in controlling the hearts and minds of the oppressed.

The cultivation of ignorance and pseudo-knowledge in the minds of the oppressed was one of the most potent weapons of conquest. Epistemic freedom, therefore, becomes a potent decolonial tool. It becomes the ultimate freedom to be free for the people of the Global South.

The Decoloniality of Epistemic Freedom

In elaborating his thesis on Epistemic Freedom, in the book, Epistemic Freedom in Africa: Deprovincialisation and Decolonisation, of 2018, Gatsheni describes it as the critical freedom of the people of “Africa to think, theorise and interpret the world from where they are located, unencumbered by Eurocentricism”. In other words we should think freely from the standards and prescriptions of Empire if we are to decolonise our minds and unmask coloniality. Our epistemic virtue and epistemic dignity depend on us investing freedom in our thinking modes and models. This is not good old academic freedom, or neo-liberal freedom of thought and expression, no.

This is a brave claim that as Africans we are human and we think therefore we are. We all come from legitimate histories, knowledges and humanities. We are not negotiable but are sources of the power and beauty of thinking and knowing like any people under the sun. We are discoverers and inventors, we do not claim superiority, we claim equality. We think of the world while standing in Africa and we understand African from the world. Like Aime Cesaire we are not removing and isolating ourselves from the world or are we losing ourselves in the world, we want a local that is worldly and world that is rich with our locality because we are equal citizens of the universe.

Whatever inequalities with others that we suffer, those inequalities are not natural but were constructed and imposed on us by Empire, that is what we call coloniality. It is to be epistemically free to know that the people and the places of the Global South are not poor they have been impoverished, that as Walter Rodney said, Africa is not naturally undeveloped it was underdeveloped by Europe. Epistemic freedom, in that way, is decoloniality that has lost its temper that rejects colonial myths, stereotypes and propaganda. Did Bob Marley not put it well when he said: “They think what we know is only what they tell us!” Epistemic freedom is knowing what we were not told, in other words.

Cetshwayo Zindaba Mabhena writes from Braamfontein, in Johannesburg: [email protected]