The Sunday News

Phathisa Nyathi

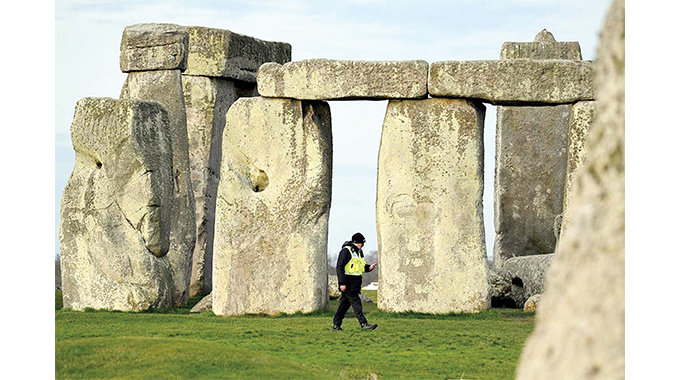

THE presence of phallic objects and their female counterparts at Stonehenge was explained in terms of the desire to express the concept of continuity and relate it to eternity and spirituality. A gory story is presently doing rounds not very far from Bulawayo.

A young man was picked up in the morning on the tarmac road with his testes missing in a suspected ritual killing orgy. Apparently, the corpse was abandoned on the tarmac to create an impression that the deceased man was run over by some passing vehicle. However, health experts suspected foul play.

To those schooled in African Thought the incident does not come as a surprise at all. There are people today who share the same perceptions and beliefs with the ancient creators, builders and users of Stonehenge where phallic objects were excavated. I have said where interpretations of phenomena at Stonehenge and other ancient monuments present challenges, we only need to turn to Africa where the same ideas are still in vogue.

Sex organs are special body tissues with a capacity to replicate humans. That process of replication translates to eternity of the human species. Into cultural situations, the traits of sex organs are infused. It appears the special organs were intended for a lucrative market in South Africa where there is strong belief in the use of muthi to help businesses flourish, endure and become sustainable. It is a matter of symbolic manipulation.

Replication (read sustenance, profitability) at the level of humans is believed to translate to replication on the business front. Youthful age and accompanying sexual virility are important considerations; hence, the young are the most vulnerable.

However, today as promised last week, our thrust is on the “wings” as found on phallic objects and human sex organs. Let us start with matters sexual. What has to be appreciated is that sex among human beings is much more than a biological process, more so among the African communities.

Numerous cultural interventions impinge and affect the natural process. In the end, the process is very much both a spiritual and cultural process. It is not a “bull and cow” encounter where both “partners” are not culturally schooled. In a situation like that the process is entirely biological.

Not so with African communities and societies. One Bulawayo artiste, one Nkiwane, reminds me of a song he sang about umjolo, flirting with women. He arrived at the conclusion that umjolo ngumjolo, izinto lezi ziyafana. From my perspective, izinto lezo, kazifani. What singer Nkiwane claims is applicable only in terms of anatomy and physiology of the sex organs, for females in particular. Similarity ends about there.

Cultural interventions transform sexual act from a biological process to a bio-cultural one. It is the cultural component that accounts for the difference, making izinto lezo to be very different. To clarify the point let me give an example.

In Africa there are formulations that are used to create “virgin conditions” during sexual encounters. In the Ndebele language, that process is known as ukuvunula. Of course, non-African societies tend to despise and denigrate the practice and give a litany of side effects and term it a “harmful cultural practice” as is the case with African cultural practices in which they do not engage.

Among some communities, there are sexual lessons that are taught to women regarding how to “take it to the man.” Training known as chinamwari is engaged in where drums are beaten, music played and nails or their equivalent are placed below women’s waists so that they perform a suspended sexual dance. Then surely, izinto lezi kazifani.

However, it is all there in the language that captures our cultural experiences and heritages. The Ndebele will say, Zedlulana amambatho. This ukwedlulana amambatho led to one of a man’s wives having ingubhamazwi also known as impoliyana crafted for her. The poncho generated jealous talk among a man’s wives, hence its name.

We acknowledge that the abandonment of puberty-related training has created problems for young couples in Zimbabwe and elsewhere in Africa. To these young couples, sex has drifted more and more into a biological process.

This is because of the absence of requisite schools where young couples, even before marriage, are introduced to the cultural aspects.

A few days ago, an old woman invited me to her house. Her grandchild and his spouse who were not schooled into these matters were experiencing marital challenges. She asked me, “When should young couples engage in sex after the wife has delivered a baby?” I began lecturing her on sexual mathematics deriving from child spacing in a traditional set up where the second baby is two years younger, and the gestation period is nine months, calculate when our ancestors engaged in sex after baby delivery.

Our discussion lasted longer than two hours. Her concern was that the grandchild lost his sexual virility. Their marriage is on the rocks. I responded with a question, “Where are the schools or fora where the young are introduced to the marital pleasures, skills and obligations of adulthood?”

Anyway, let us turn to the wings and fly away. I raise the topic here because the Romans provided their phallic objects with wings. But, wings for what? Should we imagine some cylindrical light machine gun with two cannon balls flying above our heads? Africa please help! It is back to cultural intervention in the sexual anatomy and related use of same.

I need not belabour the point that I see no bird in the “Zimbabwe Bird.” Some engage in arguments whether the bird is a hungwe or chapungu. We the Babirwa may even argue that it is our dove, leheba. Unfortunately, I do not subscribe to any of these wild guessing games.

Where the moral and ethical terrain is difficult to traverse, artistes always find ways to circumvent the vulgarity. A bird certainly has wings. One characteristic of a bird is possession of a set of two wings. On the Zimbabwe Bird, the wings are very clear. So, what is the issue? We get nowhere when we look at the “wings” in isolation. Only a holistic view of the entire bird illuminates the wings.

I recall not so long ago when I lectured some students from the United College of Education (UCE) whose class was predominantly made up of mature and even married. The same question about the wings was posed. I remember one female student teacher thrusting both her extended arms forward, twisting them so as to upturn both her palms.

She ended there and that was her answer regarding the “wings.” I gave her full marks as it was clear to me she knew what is meant by the “wings.” Of course, I expected one of the women to know the “wings.” Some, among them, were mature women.

Many years ago, when my cultural journey commenced, I interviewed some mature ladies about these matters. They were of Shona extraction.

They told me how in their culture the “wings” are developed in women’s genitals. A certain plant was sniffed and the sudden and intense sneezing it produced thrust forward the labia, the wings (mapapiro) in their language. In other instances, there is physical pulling which results in the labia being extended, the much-desired condition for the pleasure of men. Izinto kazifani Nkiwane!

It is the same story among Ndebele women. The lotus plant has leaves which were used to pull and extend a woman’s labia. I have been told stories where bat wings have been used to effect the same results. The lotus has found its way into the praises of the Ndiweni people, Maleb’ omfula.

What wings were the Romans referring to which they attached to the phallic objects? Phallic objects refer to the male element. The male element alone will not produce the desired result-the perpetuation of the human species. Human replication is a product of sexual reproduction, and it takes two to tango. The opposite and complementary opposites are required for the process to produce the intended results.

That missing element is the “winged” female sex organ. The “wings” were thus symbolic of a completed elemental symbolism, not wings to fly the phallic objects.

The last question has answers that my two late friends provided. Chikari, was the word Lawrence Jenjezwa used to describe the female apparatus devoid of wings. In other when there are no extended or pulled labia. The emerging picture is one of a beer drinking vessel with a uniform brim, chikari in Shona, isikali in IsiNdebele.

It was Stephen Chifunyise who referred to the “extended wings,” (read labia) as guitar strings that a man strums during sexual foreplay. It is all for the pleasure of men. Only when we get into the minds of Africans can we hope to acquire perceptive minds that will see birds as creative works of art calculated to transcend a cultural terrain characterised by vulgarity, explicitness that axiology, morality and ethics forbid.

For more on this see my book, Journey to Great Zimbabwe.