The Sunday News

Cetshwayo Zindabazezwe Mabhena

For virality the coronavirus of the present is only a scary addition to many other pandemics that have been bedevilling humanity for a long time now. Those philosophers and activists of the world that have concerned themselves with thought and struggle against all forms of domination and oppression know it only too well that there are many viral pandemics out there. The pandemics might differ in virulence and virality but they remain violent ghosts that advance a haunting presence.

The pandemic that my present consideration is concerned with is the virus of racial hate and the many evils that accompany it. Racial hate has not only appeared as the obvious and declared persecution of one by the other on what EWB Dubois called the “colour line,” no. It has taken on many other guises that involve the division of the planetary human family, and discrimination of certain members of it according to their geographic origins, nationality, religious belief, gender identity, history, culture and political conscience.

Racism is a monstrous, many-fingered octopus that travels around wearing a multiplicity of masks and myths. It is, as a system and a structure of hate and oppression, very good at calling and presenting itself by other names and even means. For that reason it may take some discerning and a little critical consciousness for one to be able to unmask, notice and name racial discrimination and its hate and violence.

Who is afraid of Achille Mbembe?

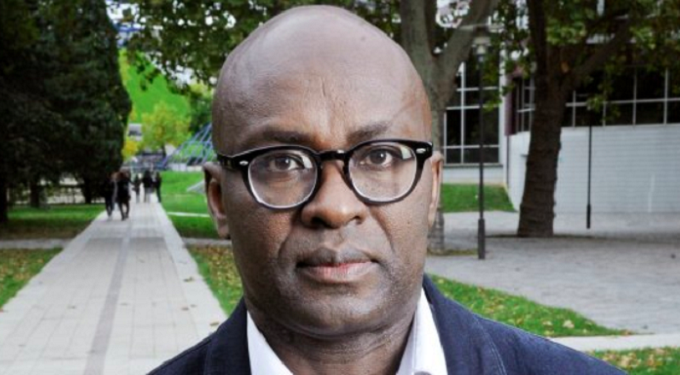

In the global academy Achille Joseph Mbembe is surely a man about town that does not require lengthy introductions. His historical and philosophical meditations, in form of books and journal essays, appear in French, English, Germany and I think some other languages. The accident of birth placed Mbembe in Cameroon some 60 years ago if I am not mistaken. He is presently a research Professor at the Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research (WISER).

What has given Mbembe intellectual fame is not only his novel analytics, rigorous observation and philosophical depth but also his poetic and sometimes musical expression and description. One can summarise Mbembe’s intellection as a mixture of force of analysis and beauty of rendition. Well-read, informed and brave Mbembe is frequently prophetic in his descriptions and gestures that habitually swim against the tide, questioning dogmas and proverbially pulling down even ancient monuments and statues, in stubborn iconoclasm.

It is no accident that one of Mbembe’s books: On the Postcolony (2001), was argued by one observer to be the most stolen book in libraries and bookshops of the world. I have witnessed this for myself in that a dear brother and friend of mine that hides somewhere in the corridors of the Midlands State University borrowed my latest edition copy and then methodically converted into a detail of his vast personal library. I have forgotten but not forgiven, waiting my chance to invade and loot his library royally. This a solemn promise Bra wami, with my Pakol on my head! This might just be a small drama that is a perfect metaphor of how far the philosophical thought of Achille Mbembe has gone in causing some kinds of intellectual and political civil wars, creating cliques, provoking cults of love and hatred here and there.

The excommunication of a thinker

The word “excommunication” which refers to the removal and expulsion forever of a rebel from a religious community was last used by Amos Elon in 1963 in reference to the anger and hate towards Hannah Arendt. The smoking and thinking girl had published essays about Adolf Eichmann, Hitler’s chief gaoler, which questioned both the Nazi and Jewish leaders regarding the sin of the Holocaust. In 2016 Mbembe, among other essays, published: The Society of Enmity.

In his now familiar descriptions of domination and hate at a planetary scale Mbembe compared Israeli persecution of Palestinians to South African apartheid evil, and judged that the persecution of the Palestinians was worse. Mbembe drew a picture, in words that exposes the paradox of how the Jews that were victims of the Holocaust were now victimising others. Before Mbembe, Edward Said attracted ire when he described the people of Israeli occupied Palestine as the “victims of the victims.” He was called a “Professor of Terrorism” par excellence.

Tersely, Mbembe in his own account noted that in the past “Negro and Jew were once favoured objects” of racial hatred. And “today Negroes and Jews are known by other names: Islam, the immigrant, the refugee, the intruder, to mention only a few.” The account is chiefly about hatred and enmity in the planet. We live in a world that cannot do without hated and feared enemies. If they are not readily there they are systematically invented so that they can be hated and violated with impunity. True to my previous instalment of this column these enemies are not punished in the name of hate, no, the punishers declare themselves the patriots that love the motherland, sometimes the holy land, and the nation. They claim to be duty-bound to clean and purify the nation, religion and civilisation of some pollutants that happen to be other human beings, tragically.

Some agitators in Germany quickly concluded that Mbembe was an anti-Semite, and in that part of the world this is a grave allegation. An invitation to deliver a Keynote Address to an arts festival that Mbembe had received was questioned and challenged. Concerned African scholars cried foul out loud. Other scholarly individuals and communities of the world noted the attack on academic freedom, freedom of conscience and of expression. Some insisted that Mbembe was an “anti-Israeli inciter.” Among his protests against the allegations Mbembe politely but tersely asked all concerned to read his work, and not fish out a few sentences out of context, as the work speaks for itself and its critical humanism is obvious.

Troubling questions

Several other scholars that include Jewish thinkers have questioned the evil and impunity of the State of Israel in Palestine and they have not been called anti-Semites. So is it because Mbembe is black and an African? Empire in the past and the present has not suffered well a thinking black person. Mbembe should be particularly irritating as a fluent black body that speaks of the world and humanity as if reading from the very back of his hand. Frantz Fanon told us how the conqueror and the coloniser believe that “the black man that quotes Montesquieu should be kept under surveillance.” The allegation that Mbembe relativises the Holocaust begs another question.

Does it mean that people like Mbembe and some of us that hail from histories of slavery and colonialism cannot be allowed to compare and contrast violences of the world, including the Holocaust? That the Holocaust should not be compared to any other crimes and violence, to us the enslaved and the colonised, sounds like Holocaust exceptionalism, which may suggest that violence committed by white-skinned people on other white skinned people is elevated beyond thought and comparison which sounds racial. Aime Cesaire in: Discourse on Colonialism (1955) noted tersely that in the Holocaust violence that was reserved for the Coolies of India, Muslims of Algeria and Blacks of Africa was for the first time practised by Europeans on other Europeans, and that was the paramount scandal for white supremacists.

The white supremacists might be of the habit and the impression that their imagined superiority means that even their evil is superior and must not be downgraded to other evils. Democracy and liberal thinking, not even decolonial thinking, suggest that to critique the excesses of the State of Israel should not simplistically be taken to mean that the critics wish Israel did not exists as a state. The critics, such as Mbembe, only mean that Palestinians also have a legitimate right to be free and happy under the roof of the planet. There is no political or intellectual profit in defending Mbembe for being led to the cross of crucifixion; that is the homework that his work does for itself. As a philosopher whose stage is the planet and subject the human condition, crossing geographic and epistemic borders should be stock in trade, baptisms and crucifixions included.

Cetshwayo Zindabazezwe Mabhena writes from Gezina in Pretoria. This article is a shortened and simplified version of a presentation to the African Cluster Digital Roundtable of the University of Bayreuth in Germany, 9 July 2020. [email protected].