The Sunday News

Pathisa Nyathi

ART is a form of communication, both among literate and the so-called illiterate communities. As a cultural expression, art conveys the traditions, historical experiences, beliefs, philosophy and worldview of the artists and their broader communities. An African artist, is a member of a group-based community, expressed and operated within the confines of the artistic traditions of his or her community.

When communities interact with the broader environment they quite often fall back on experiences gleaned through earlier interactions. Inevitably, there should be a record of these interactions in order to avoid re-inventing the wheel and the resultant waste of both resources and time. Documentation comes in handy to fulfil that role. Without exception all communities do document their experiences. What may vary from one community to the next is how that document is done.

Two-twin projects were recently conceived by three people all brought together by the love and passion for the arts and culture particularly in the rural areas of Matobo, within the Matobo Natural/Cultural Landscape or World Heritage Site (since 2003). The three people in question are Veronique Attala, Professor John Knight and this writer. The first project, dubbed Comba Indlu Ngobuciko, My Beautiful Home, is about decorated houses, and was launched within Matobo Rural District Council’s wards 16 (Vulindlela) and 17 (Dema) under the jurisdiction of Chief Malaki Masuku.

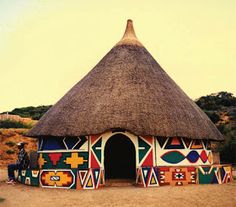

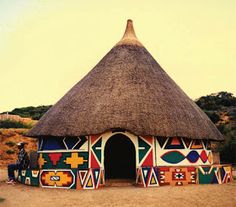

For centuries communities in the Matobo area have taken advantage of the surfaces provided by their huts to execute message-filled artistic expressions as a way of adding aesthetic value to their homely environments. House architecture allowed for the execution of beautiful designs and motifs. While the mud walls performed some utility function first and foremost, they were secondarily carriers of art. Art assisted the walls to perform their function better and at the same time fulfilled the artists’ craving for artistic expression.

The onerous task fell within the purview or domain of women and girls who always came up with exquisite and tantalising artistic renditions within the sections of the home that constituted their space. Here they captured their interactions with the environment, matters of the heart, cultural scenes and documentation of the abundant flora and fauna.

However, it has been noted that the artistic tradition, passed on from one generation to the next by oral means is facing a serious threat from urbanisation and globalisation. Architectural traditions are changing in design, style and type of construction materials. Painting by brush has eroded the artistic tradition that has for centuries been executed through the use of hands. The knowledge and skills associated with hand-painting are facing a decline. Fewer and fewer women are participating in the winter-time artistic activity.

Walls were made from mud during a three-process activity: ukubumba, ukubhada and ukugudula. The first involved the use of pudlle mud to create the initial wall which was then plastered over-ukubhada and the final finish, ukugudula was achieved through the application of a watery mud mixture. That process known as ukugudula provided the fine surface over which artistic designs were executed.

The old designs, some handed down from earlier generations, have lost the meanings or interpretations associated with them. Women artists continue to execute these designs despite the loss of messages that they once carried. It is imperative that the artistic tradition be revitalised or safeguarded within the context of the Unesco Convention on the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH).

Women also executed designs on the floors of their huts. The original soil was removed and replaced with clay that was then sprayed with water and compacted. A small smooth stone was used to polish the surface till it was shiny. A watery mixture of cow dung was then applied by hand and in the process women came up with stunning designs that were pleasant to the eye. Within the two wards surveyed only one hut floor had designs. However, this artistic tradition was not part of the competition.

The three organisers decided that this year only those women who had decorated houses would take part in the competition. The measure was calculated to serve as some kind of baseline survey or situational analysis to both quantify and qualify the status of hut decoration tradition in the Matobo District’s two wards. When, in future, after the intervention of the project that is envisaged to become an annual event, there is some noticeable positive change, it can justifiably be attributed to the intervention of the project.

In order to generate interest in the artistic tradition prizes were solicited and generously given by several corporates: Kango, Fortwell, Halstead Brothers, Freight Consultants, Icrisat, Matopo Research Station and Squeaky Clean. On 12 September 2014 at Amagugu International Heritage Centre, there shall be held a prize-giving ceremony for the winners from the two wards. The intention is to progressively take on board more and more wards till the whole of Matabeleland South is incorporated. In the long term more provinces could participate.

On the day when prizes are awarded there shall be held another artistic competition, that of painted faces. The competition is dubbed Bhudaza. The verb bhudaza comes from the noun isibhuda meaning the traditional coloured paint that was applied on the faces of women and girls. The facial artists knew where to extract the colourful soils or stones (which were crushed into a powder and mixed with fat or oil). Breath-taking images were executed on the faces.

Artistic patterns were designed and executed on the women’s faces in line with African aesthetic traditions. During festivals and other joyous events women and girls sported the wonderful designs. Once again, the designs were an expressive form that provided women with spaces where they expressed themselves. The miniaturised world of human experiences and social critiques was expressed through artistic renditions on the faces of women. Women’s faces thus became mobile gallery.

We have observed that the tradition of painted faces is facing threat from alternative body art practices from other cultures. The decline in the artistic tradition has meant a reduction in the women voices. There have progressively been less and less spaces where women can express themselves.

Revitalising the artistic tradition will hopefully provide more women with appropriate spaces where they can express inner feelings and comments on the world that they live in. Hopefully, with more women participating, their levels of confidence and motivation will be enhanced and thus equip them to tackle more challenging daily issues with vigour and zeal.

It is hoped that with increased rural women participation the process of democratisation and empowerment will be pushed a gear or two up. The present will, through the ubiquitous art form, be documented and serve as a motivating springboard into the future, a future that shall be faced with full confidence deriving from a sense of fulfilment, cultural identity and a newly found sense of direction and purpose.

Research results in a better understanding of the situation under scrutiny. Beyond the prize-giving day there is a lot of scope for research into the materials used in hut decoration and face painting: the messages carried by the motifs and designs, methods of executing the designs and the compilation of research findings into a book or catalogue.

A revitalised cultural practice brings in its wake some related intangible cultural heritage. Through the revitalised artistic tradition more and more of our past is accessed and the present is domesticated so that the future is better illuminated and thus better understood and tackled.

Furthermore, the project has brought to the fore the fact that hitherto there has been undue emphasis on the arts in the urban areas — a colonial heritage and paradigm that are difficult to shake off. Arts and cultural institutions are concentrated within the urban set-up. The rural areas where the majority of the people live are generally sidelined. This rural-based project provides the scope and opportunity for migration from the colonially induced development paradigms.

The project has made clearer the link between African art and architecture. The functional walls of houses have provided women with surfaces and more critically spaces on which to execute artistic motifs and designs with deeper and sometimes more subtle meanings. While the project allows for the empowerment of women, it simultaneously affords tertiary institutions particularly those offering the Built Environment in their curricula an opportunity to work within the rural communities — studying their artistic traditions, current trends and their architectural traditions and the interaction between art and architecture. Architecture is indeed a creative and expressive art form. The result will be enhanced and more fruitful interaction between rural communities, tertiary institutions and the rural-based arts, culture and heritage institututions such as Amagugu International Heritage Centre.

It is the rural communities that stand to benefit from innovative strategies deriving from the interactions and researches going on within their communities. Issues of ventilation and lighting are very much alive within the rural architectural traditions. For example, the interior of kitchens, the roofs in particular are thickly covered in grotesque and unsightly soot, isinyayi. New and innovative designs are called for, which designs will seek to alleviate current challenges, which is the very hallmark of research.

Finally, we are hopeful that in the long term the project will render dignity and respect for traditional architectural forms which are, in any case, less expensive. Negative perceptions about traditional construction materials and house designs will have to be challenged left, right and centre so that advances in African architectural traditions are informed by traditions from the past and shaped by research which seeks to improve existing traditions. Then, and only then, can human development “march resolutely and confidently from roots to branches”.