The Sunday News

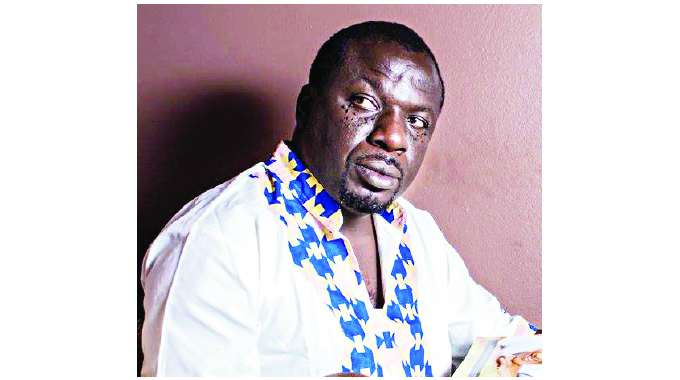

Richard Runyararo Mahomva, Pivot

Title: Shut Your Eyes and Run

Author: Raisedon Baya

Publisher: David Sling

All writing emanates from a defined philosophical standpoint. Likewise, all reading is from a particular ideological tilting or disciplinary perspective. To quote my intellectual Godfather Tafataona Mahoso:

“The perspective of the hare is different from that of the elephant, just as that of the lion is distinct from that of the crocodile; to assume a totem is to assume a perspective in the universe. This perspective is further modified by whether one is facing East, West, South or North, while in the circle.”

Mahoso’s definition of perspective as a locus of reason in the writing or reading of any society and all literary imitations of reality is critical in understanding Raisedon Baya’s latest offering Shut Your Eyes and Run and this very review piece.

My political science pivoted reading of Baya’s book is certainly not devoid of my rudimentary interface with Literature in English. As such I choose to read Raisedon Baya both as a Literature in English and Political Science disciple. This review serves as a cross-pollination of my acquired passion for political theory (an ancient field of political science) and my abandoned, but time immemorial inclination towards creative writing.

Drawing from the wisdom of Ngugi wa Thiong’o, writing is a societal self-reflective process which in all essence is political. To this end, all writing is political. The follow up to this assertion is an important question; are writers politicians? Dambudzo Marechera gives a comprehensive response to this interrogation as he states that:

“I don’t know that the writer can offer the emerging nation anything. But I think there must always be a healthy tension between a writer and his nation. Writing can always turn into cheap propaganda. As long as he is serious, the writer must be free to criticise or write about anything in society which he feels is going against the grain of the nation’s aspirations. When Smith was ruling us here, we had to oppose him all the time as writers — so, even more, should we now that we have a majority government. We should be even more vigilant about our own mistakes (Marechera 1985).”

Based on this Marecheran view, writers are indeed political players because their penned emotions either support or denounce contested constructs of power; affirm and challenge certain norms and values. All writing postures the contrasts of being, power and society in general. Writers are incessantly involved in the exercise of idea contestations, the same way politicians contest for power.

Reading Shut Your Eyes and Run imposed the need to politically make sense of Rushmore’s youthful adventures growing up in a post-colony. Rushmore who is the master narrator in Baya’s book is a symbol of the post-colony’s failure to be truly independent of miscellanies of everything imperialist. The setting of the book is Bulawayo’s oldest township of Makokoba. Rushmore’s narrative is acutely situated in the real ghetto experience — the ghetto is, by all means, a symbol of the subaltern classing of being.

Based on Baya’s account, the ghetto emblems poverty, ditched dreams, high sexual immorality indexes, violence, marginalisation and other social ills. All these cancers of society articulated in Baya’s book also express the degeneration of power and the lack of moral will to create habitable post-colonial existentialism.

The colonially inherited nations, cities and townships epitomise the transferred burden of a humanity in crisis. To this day, the antiquated state of Makokoba is representative of the timeless afflictions that signature all African townships all over the world.

Over the years, the struggle to be human and break away from the entanglements of the zones of non-being especially the ghetto continues to be the defining premise of the Black right to exist. The call for reparations by Africans in the Global North is a broad symbol of the yearning by Africans to exit the many sites of Black oppression.

This explains why we remain philosophically savaged to the obvious that: ‘Black Lives Matter’.

What Raisedon Baya laments today about the Makokoba state of being is not detached from the Makokoba which Yvonne Vera wrote about in Butterfly Burning. The same themes of poverty, moral decadence and bitterness of township life in Vera’s book are also recurring in Raisedon Baya’s 2021 book.

Baya’s work cannot be detached from Marechera’s visualisation of the ghetto as a breeding space for hope and misery. Baya and Marechera’s accounts have a common feature and a pertinent theme of exiting the ghetto in the hope for greener pastures.

The last story titled Farewell in Baya’s book somehow carries the entire style and the thematic import of Mercy Dliwayo’s 2020 publication Bring Us Back Home. The constant interface between impoverishment and hope for livelihood change from poverty courtesy of migration exposes the continued search for better prospects beyond the border zone.

This is a reality that dates back to the infamous Wenela days. In a way, the crossing from one border to another by the ordinary citizen exposes the number of opportunities scattered across the continent. As such, our walk in the search for opportunities and self-betterment is a perennial process.

To this end, we see pan-Africanism being in continuous motion as the citizen’s search for a better becomes a common cause to break the Berlin designed border barrier across the continent. At the same time, pan-Africanism suffers the toxicity of xenophobia as periodically witnessed in South Africa.

The first story titled ‘initiation’ is Rushmore’s recollection of his first sexual encounter which welcomed him to ‘manhood’. It is asserted that before his sexual baptism, he was not regarded as a man. It was after some arranged sexual encounter with a minor, Muhle that he was graduated by his friends into the ‘real manhood’.

In Baya’s narration, manhood is a peer-pressure guided construct of being sexually active. Participation in sexual activity is thus a means of social validation. As such, the boy child must sexually express himself to be embraced as a ‘real man’ among ‘other men’. Likewise, Baya problematises how the moral route to acquiring manhood is not valued.

This is made more apparent by the fact that a male adult can corrupt the innocence of a minor female and is not criminalised. In reverse terms, the book exposes how adults can be sexually corrupted by more sexually exposed teenagers as is the case with Rushmore and Muhle. The transactional sexual affair between Muhle and Rushmore depicts at large the magnitude of social ironies we find ourselves in today. The reality of reverse sexual abuses is alarming.

Yvonne Vera

In politically symbolic terms, Rushmore’s sexual initiation can also be noted in the manner Africa has been peer-pressured by colonial standards to adopt self-harming political behaviours. The institutional facades of colonial belonging have served as an incentive for Africa’s imposed association with colonial interests.

Rushmore personifies the desperate desire to fit into colonially acceptable forms of self-captivities. This is emphatically underscored by Africa’s financial and philosophical dependence syndromes to colonial powers.

The unaccounted but highly insinuated age gap between Rushmore and Muhle in the storyline underscores the many unnoticed — if not ignored and normalised cases of sexual abuse of minors by adults.

However, one wonders how Muhle gets to initiate Rushmore into the pleasures of the bedroom? Baya abstractly indicates how and where Muhle acquired her bedroom expertise?

The reader is left to a gamut of assumptions. This narrative gap can be engaged through the instinctive imagination of Muhle as an orphan since the writer does not bother to tell us about the young girl’s parents. She is virtually parentless in the text.

Ironically, today one wonders where the West derives its moral credence to parent African democracy, governance and diplomatic decorum. Muhle is also the reason why Rushmore’s graduation into manhood is punctuated by a Sexually Transmitted Infection (STI). To this end, the West’s unaccounted interference with the continent’s self-determination serves as the major reason for Africa’s political-economy infections.

The tragic part of Rushmore’s manhood graduation is synonymously symptomatic of the “half-baked” independence of Africa and her ceremonial farewell to imperialism. However, in a more literal sense, Rushmore’s chastity escape brings to the fore Dambudzo Marechera’s critique of the ghetto and its promiscuities:

“There were no conscious farewells to adolescence for the emptiness was deep-seated in the gut. We knew that before us lay another vast emptiness whose appetite for things living was at best wolfish. Life stretched out like a series of hunger-scoured hovels stretching endlessly towards the horizon. One’s mind became the grimy rooms, the dusty cobwebs in which the minute skeletons of one’s childhood were forever in the spidery grip that stretched out to include not only the very stones upon which one walked but also the stars which glittered vaguely upon the stench of our lives (Marechera 2009:30-31).”

The raw images of sex and sexuality in Baya’s story depict Achile Mbembe’s aesthetics of vulgarity which are defined as the institutional perpetuities of the colonial in the post-colony. Makokoba is thus a motif of the colonial vestige expressed in the poverty, marginalisation and dehumanisation of a people.

In the process, the normalcy of the abnormal becomes normal. The sexual drama in Baya’s book is evident of the raw immorality playing out itself in our eyes daily, thus invoking the urgency to keep fighting to run away! But a pertinent question arises, for how long will we keep running from the burden of history until Africa’s freedom is realised? This question even gets louder in the conscience of our liberation agenda as this year’s Africa Day celebrations on 25 May are fast approaching.