The Sunday News

Literature Rethink with Richard Runyararo Mahomva

In the last two weeks, the spine of my submission has been the demand to decolonise the university in Africa and defining its function along Afro-centred terms. The previous series was inclined to issues of epistemic refurbishment of Africa’s tertiary institutions. This seemingly radical route of epistemic disobedience is important considering the captivity of our tertiary institutions by forces of coloniality.

As a result, they have failed to become practicable drivers of the continent’s yearning for decoloniality. As clamoured in Taiwo Olufemi’s clarion call “Africa must be modern”, the university must be modern in its pronouncement of liberation from the residues of Western hegemony. In this anticipated dispensation of decoloniality, to be modern must mean de-westernising African socio-economic and political institutions of development.

For the benefit of other readers who missed the two previous articles, let me hasten to highlight that African nativism has been evolving from one epoch to another.

African nativism has never been stagnant as most proponents Western thoughts want us to believe. This is the reason why we speak of nationalism and pan-Africanism as “movements” of Africa’s generational liberation. In its multi-faceted character, African nativism has tactfully confronted the changing adversities of the Global-South’s freedom from that generation to this generation. Likewise, African nativism has changed faces, but a similarity shared by all nativist vanguards is their ability to produce top notch epistemic treasure troves which crystallise our goals for liberation as the oppressed of the world. To that effect Sabelo Ndlovu-Gatsheni (2008: 16) notes:

“There were of course those Africans like Joshua Nkomo, Leopold Sedar Senghor and Jomo Kenyatta who developed a ‘romantic’ love for the precolonial African cultures and tried to mobilise these to pothole colonialism. But overall the African bourgeois class ‘accepts the principles implicit in colonialism but rejects the foreign personnel that ruled Africa’ (Ekeh 1975: 96). But to justify their rightfulness to replace colonial rulers, the African educated elites resorted to nativism which they intermingled with their anti-colonial ideologies, which Ekeh described as ‘interest-begotten reason and strategies of the Western educated African bourgeois who sought to replace the colonial rulers” (Ekeh 1975: 100).

The epistemic wealth inherited from fathers of African decoloniality significantly dates back to the time of Marcus Garvey, Kwame Nkrumah, Leopold Senghor, Julius Nyerere. Even today, this literature still constructs the Global-South’s political-economy ideological underpinnings. Sabelo Ndlovu-Gatsheni (2008:7) further points out that:

“. . . the logic of colonialism . . . became an inevitable part of African liberation discourse. From Octave Mannoni (1950); Frantz Fanon (1952); Albert Memmi (1957); Frantz Fanon (1963); Ashis Nandy (1983); Ngugi wa Thiong’o (1986) right through to Mahmood Mamdani (1996) and Achille Mbembe (2001) the issue of the epochal impact of colonialism on the African mind and on the invasion of African imagination has been emphasised. The psychology and praxis of colonisation had devastating impact on the evolution of African political consciousness including imaginations of liberation.”

The above view reflects how the post-colonial experience produced filial nativist ideas of being African through the pen. This was because the pinnacle of African consciousness was clear enough in terms of expressing the true meaning of breaking the umbilical cord between the colonialist and the colonised. These ideas of liberation captured in the written word became the mobilising tool for resistance to colonialism and its dehumanising effect to the colonised.

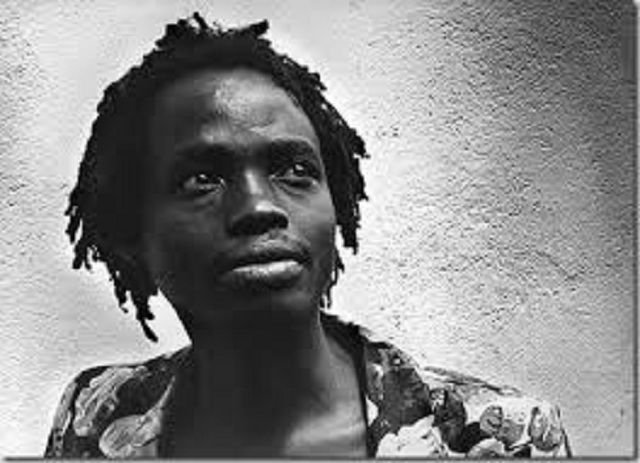

Dambudzo Marechera — the African writer with no identity

On the opposite extreme, there was a rebirth in appreciating oneself as an African. Contestations on the idea of Africa and the consciousness thereof also emerged as a result of identity bastardisation which was a product of Africa’s colonial experience.

This was the outgrowth of education in coloniality or the mere neo-colonial liberal trajectory revolving around falsehoods of ‘free-thinking’ and exploring the fluidity of identities. This exposition comes out clearly in the writing of Dambudzo Marechera who defied the traditionalised idea of being an African writer as depicted in the works of other combats of the pen like Ngugi, Achebe, Soyinka, Ayikwei Armah to mention, but a few. In an observation by Marechera’s ex-lover and Germany Professor, Flora Veit Wild (1987: 113):

“Dambudzo Marechera is an outsider. He cannot be included in any of the categories into which modern African literature is currently divided: his writings have nothing in common with the various forms of anti-colonial or anti-neocolonial protest literature, nor can they be interpreted as being an expression of the identity-crisis suffered by an African exiled in Europe.”

Marechera’s brutal contact with Europe made him feel cultureless. Instead of humanising him, Marechera’s contact with the West made him less of a humanised African. Marechera is a clear template of Europe’s failure to create wholeness for members of its erstwhile oppressed classes human-beings. Marechera’s intellectual uniqueness could be better retraced to denialism of the self and rejection of his humble African socialisation which he began to deconstruct after his contact with Europe. Flora Veit Wild (1987: 113) further notes:

“Marechera refuses to identify himself with any particular race, culture or nation; he is an extreme individualist, an anarchistic thinker. He rejects social and state regimentation — be it in colonial Rhodesia, in England, or in independent Zimbabwe; the freedom of the individual is of the utmost importance. In this he is uncompromising, and this is how he tries to live.”

The above characterisation of Marechera clearly demonstrates that the man had gone beyond what W. E.B DuBois referred to as “double-consciousness” — a state of an individual’s identity fragmentation into numerous fragments. Double-consciousness makes it difficult or impossible for the individual to have one integrated identity. This internal conflict experienced by subordinated individuals like Marechera and all the colonised manifests as a psychological deficit of “always looking at one’s self through the eyes” of coloniality while battling with reconciling with African socialisation. In other words double-consciousness is a spiritual striving and in local terms double-consciousness is equivalent to mamhepo/imimoya. It is a search for the dismembered soul of the oppressed, the dehumanised, vanquished and all the bottom clustered members of the coloniality human hierachies.

The effect of internal strivings and personality multiplicities is evident in the above description of Marechera. He is said to have been an “individualist” which may loosely refer to one who places the self before the rest and cares not about others. This attribute places Marechera in the periphery of the “I am because we are” African social order. This description denies him the fundamental attribute of being African, since we are a people whose role is to replicate values of our society and not the self.

This is proverbially echoed in Ndebele philosophy: “Umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu”. This Ndebele adage simply explains that an individual’s character is shaped by maxims of their society and likewise, Shona wisdom proclaims the same “Munhu, munhu pavanhu”.

On the other hand, the concept of “individualism” is synonymous with Eurocentric perspectives of capitalism which dismembered Africa. Moreover, Marechera’s description as an “anarchistic thinker” dismantles the ubuntu/hunhu values which are expected of every African and most importantly African pen heroes in grappling with colonialism as a primordial anarchical order. The consciousness of “being” within categories of nationalism and pan-Africanism are said to have been absent in Marechera’s epistemic wholeness “— be it in colonial Rhodesia, in England, or in independent Zimbabwe” Flora Veit Wild (1987: 113).

Therefore, comprehending his contribution to literature through lenses of decoloniality becomes a problem though he remains a hero in his own right. However, there is need for Marechera to be read from a decolonial perspective to locate whether his legacy belongs to Africans or the White society.

This is because Dambudzo Marechera is celebrated in institutions which under-valued Black ideas and knowledge(s). His education at Oxford University clearly substantiates that fact not to mention that he was the only African writer to win the Guardian Fiction Prize. The same applies with other writers who have resorted to denial of the African struggles to find belonging in spaces where Africans are unwanted.

A new wretched of the earth

Marechera represents a lost-generation of Africa’s intelligentsia. He is a representation of the mythical ‘born-free’ whose education has failed to make them decolonial beings. Their education has further exiled them from their African socialisation which they perceive as highly denigrating. Unlike, the first version of the “Wretched of the Earth” pronounced in Fanon’s decolonial meditations, Marechera’s life through the pen replicates the worst.

His work speaks clearly to a physically “born-free” generation which has a colonially devalued intellect. This generation’s devalued acknowledgement of “being” is a result of grappling with internalised coloniality while at the same time trying to reconcile with one’s aspirations to be truly free. These are the “liberated African” with little — if not any recall of armed struggles of their respective mother countries and it’s not their fault that they arrived late in the world to be the children of the oppressed. Some of them were born during the transitional periods across the entire continent when their nations were preparing themselves for independence.

While others like me were born many years after their respective countries’ struggles for freedom. These half and full “born-frees” are the new wretched who happen to be beneficiaries of bankrupt Western knowledge which has failed to humanize them to be “real” African intellectuals. They are caught up in the entrapments of coloniality and are well-defined in terms of aspiring to be global citizens than they are Africans. They have nothing to lose, but the Africa identity which they don’t care about. For them being African is carrying the yoke of the “oppressive” post-colonial state which they vilify left, right and centre. As a result, from time to time whenever opportunities are availed they swap national patriotism for writers’ residences in Western universities.

These great minds lost in the trap of double-consciousness find themselves in Western institutions which denigrate African political values and the post-colonial state. In return the West gives them high accolades which give them credentials to lambast African states for poor governance. These become the voice of polarisation which deodorizes Western governance styles and denigrates African leaders for failing the masses.

This is the reason why most of our writers in the continent have failed to stand firm in defending African economic development oriented policies. For instance, the launch of the land reform programme in Zimbabwe made way for demonised misrepresentation of Zimbabwe’s political environment. As a result, much of the literature that has been produced since the outbreak of land repossession from colonial ownership has portrayed the country’s political systems as barbaric and undemocratic simple because those we have entrusted with the mandate to tell our story are not one of us though they look like us. They are mercenaries produced out of the school of double consciousness. To be continued.

Richard Runyararo Mahomva is an independent academic researcher, Founder of Leaders for Africa Network — LAN.

Convener of the Back to Pan-Africanism Conference and the Reading Pan-Africa Symposium (REPS) and can be contacted on [email protected]