The Sunday News

Micheal Mhlanga

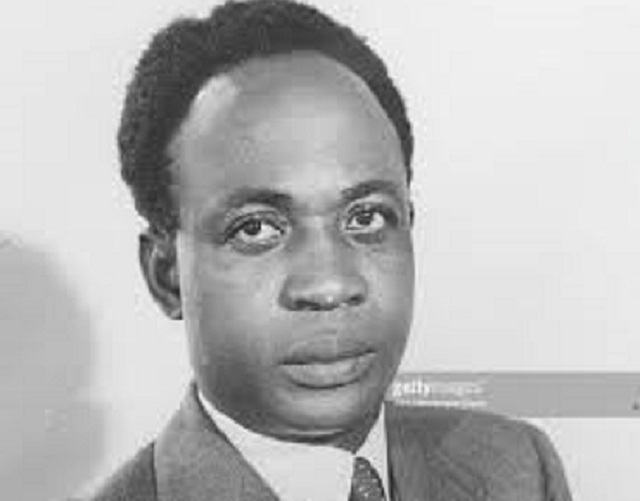

Class Struggles in Africa, a book by Kwame Nkrumah, is one read I strongly recommend to those who are struggling with the basic fundamentals of class content and the meaning of a new agenda set by the Second Republic.

To many, the comprehension of what a class is, let alone achieving the middle class economy by 2030 is prattle. This is evidenced by the recklessly thrown around economic analysis and political sophism trolling social media.

The past week is a classic example of how episcopal fanatics overnight become tutors of financial intelligence, mechanical mathematics and media demagoguery. I do not blame such a common trend, it’s a symptom of sloth and should be resolved sooner.

This second installment will argue that 2030’s success is reviving what was started in 1980 and will be a result of the state’s model of financing education which has a direct impact on the economy.

To fabricate my analysis, I am informed by the thoughts of Moeletsi Mbeki’s Architects of Poverty. I find his book relevant in reconfiguring class struggles and how a developing nation constantly misses fundamentals of development.

The Architects of Poverty

This is Moeletsi Mbeki’s book title and the basis of his argument in the 196 pages. To determine our failure, we need not look outside and attach blame to a frantic and frustrated Capitalists West, the problem lies within us.

What happened in the past 37 years was a denial that we need the rest of the world, lying to ourselves that post-independence aggression demystifies mythologies we had created about our colonial misfortunes.

In doing so, while importing incomprehensible politics of the national purse, modelled on the Westminster, which many hardly understood we could not link cultural and political economy to the fast changing global economics.

We were warped by our success immediately after independence which was sustained by large amounts of foreign aid, a trickle of private foreign direct investment, provision and access to education to the previously disenfranchised black people and the return of a well-trained black exiles.

Thereafter, geo-politics stripped us off all we survived on. The global frustration banned our leading export, asbestos, wiping out the large foreign exchange earner, consequently a huge pool of people lost a well earning job.

That is the first demise of a growing black middle class. Not withstanding the impact of sanctions, another greatest employer, the rich Virginia tobacco farming lost a valuable market, the West, which embarked on discouraging health crusades.

This pushed the gold leaf to be sold to poorer economies such as Latin America, Asia, Africa and Eastern Europe resulting in an acute drop in tobacco prices and production.

This and many other punitive global shifts on Zimbabwean exports was coupled with a growing population and a rapid response to the land question. Our noble land redistribution is one opportune action, however, we delayed in capitalising it.

We recently are recognising how Command Agriculture could have been fortunate had we implemented it in 2000, but anyway, more attention on it is a good case study of creating the desired middle class economy by 2030.

We prioritised how we differed ethnically and were left behind during global economic shifts and modern disruptions. To ratify the problem, we chose to look outside and place blame and rapture relations whilst leaving our kith and kin ravaging and plundering the little available to share.

From then, the existence of a class less economy best described us. Corruption, selfishness, an ever widening poverty-rich gap, high mortality rates, dilapidated health system, poor infrastructure, capital flight, human capital deficiency and thought-powerlessness became synonymous with Zimbabwe.

This informs why the Second Republic finds importance in creating a middle class economy for the progress of Zimbabwe.

This is a project being revived from its flop in the early years of independence. Zimbabwe is going back to the basics – what was initially promised.

Education: The pursuit of classing the disenfranchised

History tells that for Africans, an advancement in social class was the level of one’s education. In the colonial era, education was compulsory for white children and the government spent 20 times more per white student than black students. For black students, education was provided for by missionaries and not the government.

The few black children who got an education, most of them, upon employment in the prestigious white collar jobs, became the middle class. This was a class reserved for the educated blacks, Asians and mixed race. They became the elite class: those striving and struggling to be European.

Hilariously is how intelligence then, and in some instances now is how one’s English accent is more British, denoting their level of education.

The middle class then was the black British accented, today, no matter how long you have been in school and the numerous degrees you may flaunt, middle class by education is a mirage.

Unfortunately, that misinterpretation of education was carried into liberated Zimbabwe yet global forces of attaching education to financial prosperity have changed.

Even the government’s 1980 policy of “Growth with equity” which was meant to eliminate the social divide created by the schooling model then, still focused on delimitations of colonial education hence a fundi in Education, Fay Chung, said that we did not produce school leavers for the world of work.

The narrative of being educated and automatically mounting the social ladder (middle class citizens) has eloped. We constructed our own poverty by not remodelling our education system to be qualitative, but instead, although important as well, made sure that as many people go to school, albeit the quality of what they learn being colonial and frigid.

The education system we served produced employees; the reason why countless are waiting to be hired unequipped with solutions to the problem of unemployment.

This was sustained by a façade that Zimbabweans get employed easily outside, ignoring that the spaces they are easily employed have a predominantly “peasantry culture”. If you think I am mendacious, then revisit the history of Ghana immediately after independence.

A classic example, the former President, Robert Mugabe, went to Ghana for employment because Kwame Nkrumah invited educated Africans then to come and get employed because a majority of his countrymen were uneducated.

From idealising to pragmatism

Beyond that thought line, our education system has continued to enrol enormous numbers and graduates few of extraordinary eminence. Solutions to rescue our country seldom come from those educated within and that has, and is a problem. With only 38 percent being skilled graduates that begs a lot of statistical questions on the more than 15 000 who annually graduate.

What is essential from now is that state financing of education, from primary to tertiary should incentivise research on changing what is being learnt to foster quality education. While universal education is critical, it should be doubled with the quality that makes Zimbabweans not only globally relevant but skilled enough to be domestic think tanks.

The reasoning of financing education now is that by 2030, it would have stimulated a shifting culture from recommendation to solution based thinking.

In fact, the World Bank’s President, Jim Yong Kim, commenting on the Human Capital Index mentioned that global economies are sustained by a deliberate investment and protection of human capital and that means financing education to ensure quality so that development is facilitated by students of a domestic education system.

Students are the next generation of workers and 2030 is an advent of another generation- the millennials.

When government heavily finances education, particularly focusing on quality change, it will coil to individuals who can sustain the middleclass.

A primary education that is diverse enough to accommodate and nurture varying talents and invests in its teacher education will produce high school students whose six years will be spent on growing identified and specific skills that are important for sustaining a middle class economy.

For now, we have been producing academic robots, students whose priority is the number of “As” not what they can do with them. Deliberate financing of tertiary education will incentivise research, innovation, creativity and logically rich thought and manpower.

It is at this stage that not only will a middle class be sustained, but ideas of going beyond that level will be curated. A middle class economy is inevitable with this.

Till next week!

Phambili ngeZimbabwe