The Sunday News

Cetshwayo Mabhena

It is not an exaggeration that ideas rule the world. Rulers and leaders are only messengers and vessels that implement ideas to rule or misrule men and women, depending on the virtues or vices of the ideas that they are contracted to.

It is not only important that leaders choose or generate good ideas but it is also vital that thinkers take time to think about thinking itself. And society must observe thinkers. Why and how philosophers think, and seek to make their thoughts known, understood, believed and implemented is worth some consideration if we are to understand ideas. By philosophers in this article I refer not simply to academic philosophers who populate university corridors memorising, rehearsing, teaching and repeating philosophical ideas of the philosophers of old.

Those are students of philosophy, not necessarily practitioners. I do not refer to professional philosophers either, those that delve into philosophy as a scholarly discipline and occupation.

They handle and practice philosophy as any other career to earn a living. I am drawn to that tribe of thinkers that by a kind of calling and circumstantial compulsion stumble onto paradigm smashing epiphanies and bring to light previously hidden truths. These are the iconoclasts that bring down ancient truths and expose them to be the myths that they are and make nonsense of popular dogmas.

I am not about to get involved in the Olympics of what Linda Martin Alcoff has called “philosophy’s civil wars” which is what I can call “disciplinary factionalism” in the understanding of what philosophy is and what it is not. In my view, for a philosophy to achieve a life and exist as living thought it must encounter, engage with and seek to solve a human dilemma in the world.

Like their close cousins, the prophets, philosophers, in justice, should name the world, describe events and foretell possible futures. To do that they should read, think, know, write and speak on behalf of societies.

Like the prophets of old, not some sophists and money mongering charlatans of today, philosophers should be able to bring forward unpopular truths and inconvenient ideas for the benefit of progress and justice in societies. Edward Said, said that pipe smoking monster, called this philosophical duty the brave habit of “speaking truth to power,” questioning and challenging old beliefs, not just singing lullabies for leaders and vocalising hymns in celebration of power and the powerful.

Why Philosophers Philosophise

Disciplinary, professional and career philosophers engage in philosophy because they have to. They find themselves in professions and occupations that require them to engage in philosophy, so it can as well be a job to do for them to remain relevant.

Socrates made the interesting claim that he philosophised because he was “born under a sign” and received from “some god” the power and inspiration to “see” truth. Philosophers are in a way, like the prophets, seers of hidden truths.

If Socrates was a black African he was going to be dismissed as a superstitious and backward lunatic that was probably high on tobacco or worse. Africans who claim inspiration from the ancestors are not, in the present academy, taken seriously as producers of truth and knowledge because of coloniality of knowledge and epistemic racism.

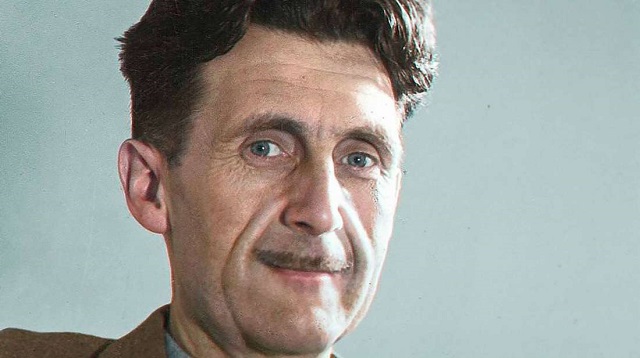

Most students, fans and followers of George Orwell concentrate on his classic novels, Animal Farm and 1984, and ignore the philosophical essays that he produced. “Why I write” is an important philosophical essay that Orwell penned in 1947. In that treatise, Orwell clarified the passions, fears and desires that compel philosophers to philosophise and articulate their philosophies. Interestingly, the first philosophical passion that Orwell noted is “sheer egoism.”

The “desire to seem clever, to be talked about, to be remembered after death” can be a major drive for thinkers as well as scientists, politicians, lawyers, soldiers and businesspeople, Orwell noted. Philosophy, in that way, can be a kind of fear of death or love for life, at the same time. Philosophers can be true attention seekers and egoists that want, through their ideas, to live and be remembered after their physical deaths. As long as their ideas live to benefit humanity, perhaps there is no problem with this human selfishness.

Other Philosophers are drawn by “aesthetic enthusiasm,” Orwell thought. The pursuit of beauty in thought, speech and writing can drive some people to philosophy. The shape of words on paper and their sound in the air can be enchanting to the philosophical mind, and that is why poets have frequently been mistaken for philosophers. Philosophy can be poetic but not all poetry is philosophical.

When words begin to be written and spoken for their sound and not their sense, their rhyme and not their reason, philosophy dies and sophistry remains. What Orwell called “historical impulse” as the “desire to see things as they are, to find out true facts and store them up for the use of posterity” is one reason philosophers are born.

Historic events, great injustices and other epical and epochal happenings may get gifted man and women to philosophical gear.

People are either inspired or provoked into deep reflection and powerful articulation of issues. For instance, Emmanuel Levinas became a prisoner of war when France and Germany fought; he narrowly survived the holocaust resulting in him becoming a philosopher on issues of life, ethics and being. Frantz Fanon encountered colonialism, as a soldier and a medical doctor. He witnessed colonialism, its violence and psychosis and became a philosopher of liberation and an activist against oppression.

Some philosophers suffer or enjoy the drive by “political purpose,” that is, they are pushed and pulled to the idea of changing humanity and the world to a certain strongly believed direction.

They fantasise of and imagine another world and spend their time, reading, thinking, speaking and writing about that world.

These are proselytisers that passionately want to convert people to some political ideas, agendas and missions, good or bad.

Slavery, colonialism and apartheid are all political and historical missions that came from the desks of evil geniuses.

For the reason that philosophers are driven to thought by many different fears, desires and impulses, some philosophies and philosophers in person can be irrelevant and frivolous. Philosophers, at least some, can spend much brain power answering deep questions that nobody asked or is interested in.

This has led to the suspicion of philosophy as a kind of madness. Many philosophers tend to scratch where there is no itch and appear like true lunatics that must not and will never be taken seriously.

Just like in science where some great inventions emerged from silly ideas, there have been world changing ideas that were produced by bored and boring thinkers that were generally believed to be mad.

Because it is a fear, a desire, a passion and a drive, philosophy can in actuality be depressing and therefore in a way maddening.

The Philosopher and his Pipe

Living philosophers are usually not taken seriously or are permanent suspects, treated as individuals that are up to no good.

Societies take seriously the engineers, medical doctors, accountants and others that, true to the demands of capitalist production, produce results that can be seen and utilised almost immediately. People want almost immediately tangible products and that is why in huge numbers they follow those prophets who perform or simulate miracles and wonders.

Maybe that is the reason philosophers end up, consciously or unconsciously, being attention seekers and performers of all kinds.

Willie Esterhuyse, the University of Stellenbosch philosopher who participated in the secret talks that ended apartheid has narrated how Thabo Mbeki floored apartheid’s trusted philosophers in the negotiations. “Let me tell you now what the ANC wants and will have by any means,” Mbeki would say.

With all the eyes of anxious negotiators, tense apartheid spies, and western diplomats on him, he would go on to pour himself a whiskey, slowly pack his pipe as they watched him, and shift to a totally new and mundane subject about the weather and the myth of beauty, ask other negotiators about their favourite books and children.

He would eat his smoke slowly for what looked like a century, before suddenly dropping a poetic political demand like “even the toughest Boer needs a hug, the Afrikaner needs love, we need a Republic of no fear where the children of the Boers and those of Africans will hug each other free of the prejudice that apartheid has created.”

Mark Gevisser diagnosed that Mbeki used the pipe and its smoke to buy time to think slowly and organise well his ideas without being seen to be struggling to think, to scratch his head.

I think Mbeki was calming agitated nerves. The anger he had about apartheid had to be balanced with a sobriety and calmness of articulation.

The wrestling match between anger and the desperate need for peace in one head can tear a mind apart.

The idea of a “peace pipe” does not only come from reconciliation rituals of Africans and Latin Americans where sharing a smoking pipe by rivals symbolised new peace and love.

Pipe smoke brings peace and settlement to a riotous mind, settles anxieties and allows calm reflection.

The American philosopher, Bertrand Russell, survived a plane crash and credited it to pipe smoking. Immanuel Kant would not step into class for a lecture without a complete draw of his pipe.

As he sat on his desk, Karl Marx looked to observers, as if he was doing more smoking than writing, especially with his strange habit of suddenly standing up and frantically walking around the room as if looking for a lost diamond pin, when he was just thinking and rethinking.

As easily as miners underground face the pollution of dust and other gases that damage their chests, philosophers as well as artistes and other mental workers face “the thinking man’s disease,” a killer scourge that comes with anxiety, panic attacks, palpitations and some bipolar disorders that trigger suicidal thoughts and all.

For centuries, philosophers have hidden behind the smoke and the peace of the pipe as an anti-depressant.

The herb that South Africans today celebrate as a recreational drug that has just been liberalised was, In Africa and Latin America, an important medical and ritual herb that leaders and elders relied on as a psychotropic aid.

Scientists, that is physicists, engineers, biologists and others build and maintain things in the world, but philosophers build and shape the world and its political direction, and they become patients of the sickness of the world.

Cetshwayo Zindabazezwe Mabhena writes from Pretoria. He is a founder member of Africa Decolonial Research Network (ADERN):[email protected].