The Sunday News

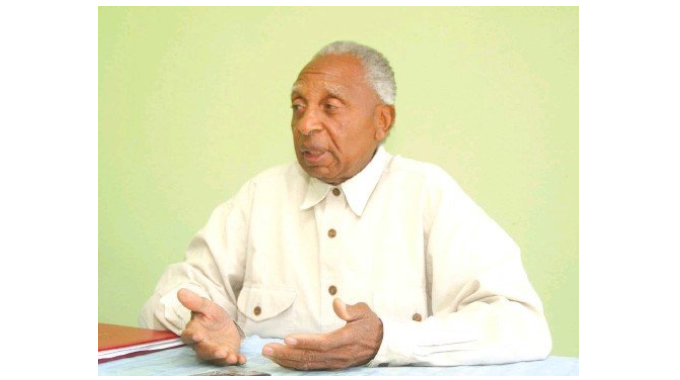

Ambassador Christopher Mutsvangwa

THE death of Father Emmanuel Ribeiro of the Roman Catholic is painful and sad.

It is also a moment to savour the bitter-sweet memories of the ongoing march of the Zimbabwe Revolution. The Zimbabwe National Liberation War Veterans Association had special bonds with Father Ribeiro. We knew and worked with him. He had an intimate engagement with the Second Chimurenga/ Umvukela from its inception, its execution, its victory and its post independent consummation. I dare say he was the living spirituality of the Zimbabwe Revolution.

His deep memory was the centralised fountain-head of the war guerrilla fighters had fought in varied war theatres as it evolved from nascence in the 1960s to a massive whirlwind of victory by 1979. The export of decapitated heads of the heroes of the 1890s war against colonial occupation marked the demise of our nation as a military power.

The response to the call to arms of the 1960s was a reversal and revival of our millennia old military tradition. This time it took a modern and potent form. Father Ribeiro, with a hidden intrepid mind, read well the signs of the times.

He deftly placed himself as the interface between a genocidal white racist minority state and its nemesis of youthful guerrilla freedom fighters animated by the grit and courageous determination of fighting a just cause for freedom, democracy and independence.

From this vantage point, Father Ribeiro would witness the wantonly murderous and crashing military apparatus of Ian Smith, the racist leader of colonial settler minority, at close quarters.

Along the process he gained an uncanny insight of how the human mind can descend to the nether depths of animalish savagery in a desperate bid to hold on to ill-gotten wealth. He saw war criminals cruelly and ruthlessly at work as their victims increased from units to tens of thousands.

Lest it be forgotten, almost every Zimbabwean family of the 1960-70s epoch has at least one relative resting inside the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. By the same token, the young Catholic priest ministered to the captured young freedom fighters of a fledgling Zanla-Zipra guerrilla alliance army in its tortuous revolution as it waged a people’s war.

Never in modern African military history has young men and women been so ready to embrace the cause of war in such numbers as the only route to national redemption. Father Ribeiro saw it all as he administered last rites to young captured guerrillas being marched to the hangman’s noose.

Along the way, he would save one lucky soul, Emmerson Dambudzo Mnangagwa. He used the ruse that he was under the legal age of execution. All because his birth certificate was not available in Rhodesia. A sure hanging by death was commuted to life in prison.

That ended up being the avenue of rescue for the death row inmate, Emmerson Dambudzo Mnangagwa. The sprouted seed of reviving the national military prowess was growing into a forest as it mastered the art and science of war.

Over the years, the exiled guerrilla leadership had continued to receive more recruits. Meanwhile, they also improved and refined their war strategy and techniques. Jason Ziyaphapha Moyo joined the ANC of South Africa allies in pitched military battles in the Hwange area in 1969. As a sequel, Herbert Chitepo and Josiah Magama Tongogara opted for a new and different approach. Taking a leaf from Frelimo, they implanted a Maoist People’s War in the North East Frontier as of 1970.

This was a quantity leap taking a qualitative dimension in confronting the colonial settler minority dominance.

African confidence got a shot in the arm when the fascist and imperial army of Portugal was brought to heel in 1974 by the collective guerrilla war of Samora Machel’s Frelimo of Mozambique, Agostinho Neto’s MPLA of Angola and the PAIGC of the late Amílcar Cabral of Guinea Bissau.

The seismic geopolitical events galvanised the frightful underwriters of imperial hegemony of Africa in the West.

They concocted the Kissingerite Detente Diplomacy of 1974 to try to forestall the emergence of home-grown African military resurgence. Every action begets a commensurate reaction. While the West was cowering, the African majority in the sub-region was sensing impending victory at last. The Zimbabwe war took yet another quantitative and qualitative leap.

Thousands upon thousands of youths abandoned school, work and normal daily life to cross the border into Mozambique, Botswana and Zambia. The quest was for the modern AK-47 automatic rifle. Father Ribeiro saw the facade of police action and criminal justice crumble.

The growing guerrilla ranks were now exposing the veneer of pretended civility on the part of an increasingly beleaguered Rhodesian army. The court system soon dispensed with assumed norms of Western civilisation.

It conceded ground to summary executions, lynchings and concentration camps termed “protected villages” or “keeps”. The next inevitable step in barbarism was wanton killings and wholesale massacres in punitive raids and revenge massacres.

The hallmark of a Western civilisation that had wrought havoc on Africa with the Atlantic slave trade and colonial subjugation, had a terrible manifest in the final days of dying Rhodesia.

A dwindling white population of 250 000 ended up with a human cull of 100 000 African souls. What a grim per capita harvest of crimes against humanity. Not to mention thousands more blinded and maimed by bullets, bombs and landmines. More were scalded by napalm and ravaged by induced anthrax and other forms of chemical and biological warfare.

What started as the lone priestly crusade of Father Ribeiro, turned into a crusade of other religious figures. Bishop Lamont and Janice McLaughlin come to mind. Catholic priests and nuns were also martyred by a Rhodesian army running amok. The Catholic Peace and Justice Commission catalogued these acts of military depravity as an expose to the world of the wider and wholesale human suffering wrought against the majority African population of Zimbabwe.

I grew up a Wesleyan Methodist from Masawi School under Chief Nyamweda in Mhondoro.

I proceeded to the Catholic Kutama College for my secondary education. The anti-British imperial orientation of the Marist Brothers from French-speaking Quebec, Canada shaped my institutional political direction.

More impressionable at personal level was the devout piety of Father Ribeiro as my catechist teacher. He accompanied his liturgical sermons with pulsating Shona compositions of drums and percussion — ngoma nehosho.

He took me in and I converted to Catholicism, to the extent that I toyed with the fancy of being ordained into the order of Marist Brotherhood. Father Ribeiro was happily relieved that I came back alive from the war at victory in 1979.

He was even more elated when I became a Minister of War Veterans Affairs in 2013. He burst into my office in 2014.

He saw my stewardship of the ministry as an opportunity to compile a true and proper history of our People’s War.

He recited a quote from the assassinated Patrice Lumumba, the short-lived Premier of the Congo, whose body was dissolved in sulphuric acid in a joint intelligence undertaking by Belgium and USA at the height of the Cold War with Soviet Russia.

“The day will come when history will speak. But it will not be the history which will be taught in Brussels, Paris, Washington or the United Nations . . . Africa will write its own history and in both north and south it will be a history of glory and dignity.” I went on to allocate a budget to Father Ribeiro’s requested project. It centred on the Heroic Seven of the 1966 opening salvo Battle of Chinhoyi. He was going to compile the stories from the families of the deceased comrades and local villagers associated with the battle.

He had also recorded the story from interrogating the Rhodesian side as the chaplain of prisons.

I lost no time in giving him official funds. I also endorsed him to Professor Hubert Gijzen the director of the Unesco sub-regional office.

Unesco runs the global project: “The Memory of the World Programme” as of 1992. The programme’s purpose being to preserve the world historical heritage. Our professional association had a short life.

The fight against the Mugabe-ist G40s took an earnest and ominous turn. Once more I soon lost my Government post as has been oftentimes. I am happy that the humble and tireless Father Ribeiro still continued with his excellent work to give Zimbabweans and posterity a history of the resurgence of their military prowess.

So much for his mind. It had the unique attribute of being the running thread connecting all that is in the crucible of the military evolution of the Zimbabwe Defence Forces, that much-cherished sword and pride of our nation.

His demise thus serves as a clarion call to our intelligentsia to endeavour to do more studies centred on our glorious Chimurenga II Revolution and the millennia-old Great Zimbabwe Civilization.

As ZNLWA we salute His Excellency President Emmerson D. Mnangagwa in conferring the status of National Hero to the illustrious Father Emmanuel Ribeiro. Both shared an abiding commitment to launch and support the Institute of African Knowledge.

Posterity needs this history for our fables and legends as a people with our own special identity. Father Emmanuel Ribeiro was much more than a Catholic priest with a parish to run and folks to deliver from sin.

May His Revolutionary Soul Rest in Peace.