The Sunday News

Pofela Ndzozi

IN this third and last segment I draw nuggets of the text and how it’s a viable prescription to reinventions of thought power in Zimbabwe.

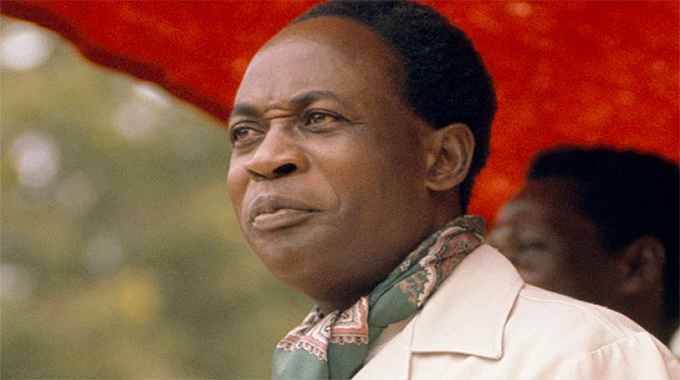

As one critically introspects 21st century pan-Africanism as an ideology and movement, it is imperative to not only reflect deeply on the visions of these two icons of this ideology, Patrice Lumumba and Kwame Nkrumah but to also draw from them standards with which to measure and audit all post-independence developments to date in Africa in general and in Zimbabwe in particular.

It is from this perspective that this chapter interrogates the goals of African independence through the lens of the Zimbabwean context.

Dr Samukele Hadebe offers a contemplative summative account of the conditions of Zimbabwe’s colonial episode and further demonstrates how pan-Africanism was and is still responsive to the objectives of the liberation in relation to democracy and patriotism.

He argues that the meaning of democracy and patriotism in the pan-Africanist context requires a definitive elaboration which is premised on the unique African experience; as such the book explores how democracy and patriotism must be domesticated within the given parameters of Africa’s disentanglement from neo-colonialism.

One of the key submissions of this book is to prescribe ways in which we can Africanise or indigenise the post-independence state.

Put differently, the authors in the seminal text propose the need for realigning principles of democracy, governance, policy architecture and social cohesion to liberation values in a bid to reinforce the values of pan-Africanism in Zimbabwe and Africa at large.

A key takeaway from the seminal text is that it is clear that African nationalism eclipsed Pan-Africanism at Independence and issues of sovereignty became the main factor. African nationalism and not Pan-Africanism led to such “phobias as nativism and xenophobia that devoured those Africans deemed to be the toxic other” (Ndlovu-Gatsheni 2013:11).

The decolonisation without Africanising the State has led to the fall into the abyss and despair by Africans. The grim situation was expressed by Edem Kodjo, then secretary general of the then Organisation of African Unity (OAU) addressing African leaders in 1978:

“Our ancient continent . . . is now on the brink of disaster, hurtling towards the abyss of confrontation, caught in the grip of violence, sinking into the dark night of bloodshed and death” (Lamb, 1983:vi).

The question to posit now with hindsight is: Should Africa had followed the Casablanca and not Monrovia block?

The Casablanca block led by Ghana under Kwame Nkrumah wanted immediate formation of the United States of Africa, while Monrovia group led by Nigeria opted for a gradual approach (Adejumobi & Olukoshi 2008:3-190.)

Another perennial question is: Did the benefits outweigh the losses in the choice by Continental Pan-Africanists to preserve the colonial boundaries drawn by the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885?

Reflect on the ethnic factor, viability issues and boundary conflicts. Actually with a United States of Africa did colonially drawn boundaries matter anymore?

The reader also learns from Dr Umali Saidi’s seminal contribution to the debate on the living idea and the decriminalisation of ethnicity in Africa.

Dr Saidi uses Zimbabwe as a case study and successfully argues that Pan Africanism offers Africa and Zimbabwe an inimitable opportunity for self-definition which transcends the colonially set parameters of framing both the continent and the nation’s decolonisation overtures.

He reckons that of note is the misrepresentation of ethnicity as the source of the conflict-ridden state of African politics. In some cases ethnicity has been abused to justify regionalism and secessionist politics where lives have been lost and marginalisation perpetuated at the behest of irrational ethnic essentialism.

Against this background, the book discusses the relevance of Pan-Africanism in engineering the structural basis for an all-inclusive and participatory social-conscience for inspiring unity, peace and prosperity in Africa.

Contrary to the cited perversion of the ethnicity question in Africa, the chapter accentuates ethnicity’s crucial role in the matrix of Pan-Africanism.

The Patriotic history debate and the role of literature in Pan Africanism cannot be avoided in the text.

Hove, Ndawana, Helliker, Bhatasara and Hadebe’s arguments posit a fundamental discourse of narrative creation and how epistemologies need to be challenged through literature particularly history.

Hove and Ndawana (p.39) argue that for too long historians have failed our people because of their timidity, sectarianism and outright opportunism.

Conditions should be created in Zimbabwe wherein a new breed of social scientist can emerge.

This class of scholars should be capable of withstanding threats and intimidation and will rise above those racial, ethnic and tribal considerations (and) oppose the suppression of any information.

A complete history of the struggle for national liberation is a long way from being produced and will only be achieved when the chroniclers of the struggle are no longer afraid to confront the truth head-on and openly, and have rid themselves of biases resulting from our recent political past. Zimbabwe’s over reliance on Professor Terrence Ranger exposes the poverty of literature and makes the African narrative vulnerable to both inside and outside abuse.

As an agent of mobilising knowledge and also leading a cohort of Zimbabwean philosophers, the reader is inspired by Vimbai Gukwe Chivaura’s tribute by Brian Maregdze. Although Maregedze does not show the link or delink of European education informing Chivaura, his submission as a prescription to reinventing Pan African thought is poignant.

Chivaura is popularly known through Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation where he hosted African Pride (Zvavanhu) among others from which many themes on resocialising the African, delinking from “Euro- North American” thought systems where dissected with other like-minded thinkers such as Claude G Mararike, Tafataona Mahoso, Sheunesu Mpepereki, Godfrey Chikowore, and Aeneas Chigwedere.

From The Patriot Zimbabwe newspaper, and his resurrection by Brian Maregedze in (p.77), Chivaura’s voice still lives on and to other disciples of Afrocentricity, Pan-Africanism, African Renaissance and thought systems challenging western hegemonic structures.

Through Brian’s rendition, Chivaura’s echoes of decolonisation of the university, knowledge systems and liberation of the African personality which are such sources of knowledges to be extracted from Chivaura’s works.

Book review: Reinventions and Contestations of Thought-Power: Emerging perspectives on Pan-Africanism Part 3

Editors: Richard Runyararo Mahomva (MSU, AU, UZ); Professor Percy-Sledge Chigora (Senior Lecturer-MSU), Dr Majahana Lunga (Senior Lecturer and Dept. Chairperson CUZ).

Publisher: LAN Readers

Publication year: 2018.

ISBN: 978-1-77906-671-8

Review by: Pofela Ndzozi (Leaders for Africa Network, Winner of 2018 Bulawayo Arts Awards Non-Fiction Literature Winner, B.A Honors Degree in Language and Communication-LSU)